Pastor Nathan Carter moved to Chicagoland for college and never left, putting down roots in the city where he and his wife, Andrea, are raising five daughters. Now, he’s leading his congregation to make a similar commitment to their city, even though it means taking on the zoning policies in a case that could have wide-reaching implications for other churches.

After the City of Chicago blocked Immanuel’s purchase of the building they’ve been meeting in since 2011, the church filed suit, claiming the city’s zoning ordinance is unfair to churches and a violation of the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA). Immanuel is currently awaiting a judge’s decision on the case.

If the church is allowed to move forward with the purchase, it will be the next step in a process that started when Carter arrived as pastor in 2004. Immanuel was meeting on the city’s north side, but in that first year, the new pastor led a re-planting effort that shifted the congregation’s focus to the neighborhood surrounding the University of Illinois-Chicago.

“We decided to not just move meeting locations on Sunday, but really recast the vision of the church to be a neighborhood church for this part of the city,” said the Indiana-born pastor. Carter grew up on a farm only two-and-a-half hours from where he lives now, but a world away, he said. During the re-planting process, Carter encouraged church members to move to the UIC community, and about two-thirds of the existing congregation did so. The Carters live in a three-bedroom home in the neighborhood.

The UIC community is a transient one—a cool place to live in your 20s, Carter said, but one that people in their 30s often leave in pursuit of good schools and suburban backyards. In 13 years, he’s actually pastored six or seven different churches, he said. “We just keep saying goodbye to people.

“But a core group is forming of young families who have caught the vision, bought houses, put down roots in this community.”

Carter and his church believe buying a building is the next step, a way to communicate to their neighbors that Immanuel is here to stay. They’ve seen lots of church plants come and go, he says, but, “We want to become a fixture in the community, holding out the gospel.”

In it for the long haul

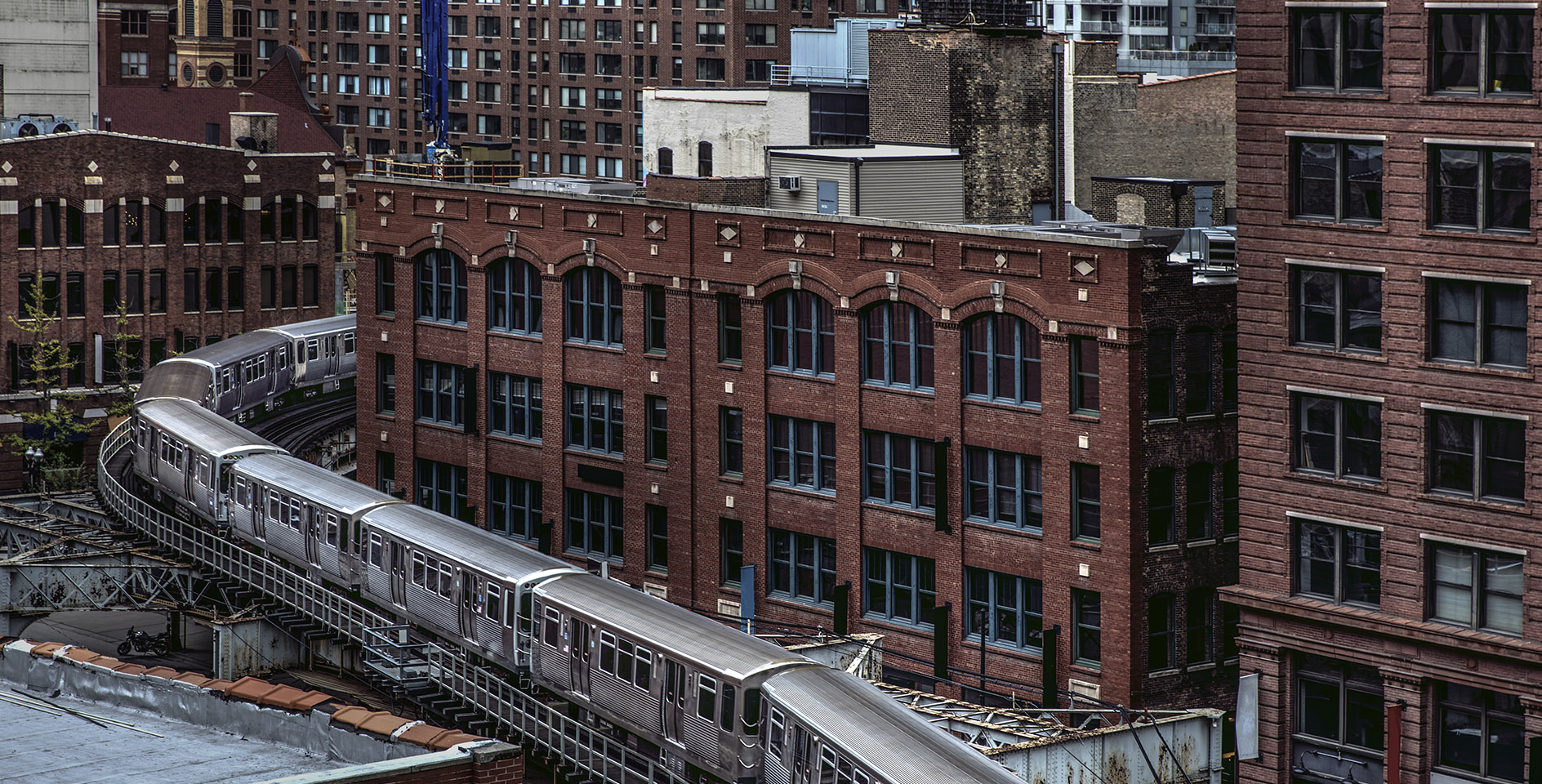

When Immanuel replanted in 2005, they met in a YMCA building that was later sold, then a school, then a second-story space they grew out of, until finally landing in their current meeting space on Roosevelt Road in 2011. The building is currently housing not only Immanuel, but two other churches that use the space for their worship services.

Immanuel started the process of purchasing the Roosevelt Road building in the spring of 2016. Under Chicago’s zoning ordinance, a church Immanuel’s size is required to have 19 dedicated parking spaces. Immanuel, however, utilizes on-street parking, a fact that city officials assured the church wouldn’t inhibit the purchase. But in July 2016, the City said Immanuel would be required to meet the parking guidelines, sparking a year-long, back-and-forth journey that is teaching his church about the biblical concept of waiting, Carter said.

A church’s vision can wane, especially when the going gets tough, the pastor said. The blocked sale and ensuing lawsuit has given Carter and his leadership team more opportunities to pastor people, and to recast the church’s vision. They’ve kept everyone in the loop through conversations, emails, videos, and social media.

If they’re allowed to purchase the building, the work is just beginning for Immanuel. The current building needs renovations, and the church also has plans to turn an additional building next door into office space, a conference room, and a kitchen.

The case could also have implications for other churches that have run into zoning restrictions, Carter said. Mauck & Baker, the law firm representing Immanuel, is arguing that Chicago’s zoning ordinance violates RLUIPA by requiring stricter standards of religious assemblies than for other organizations. Carter knows of other churches that have been negatively impacted by the ordinance. Should Immanuel prevail, it would be a big win for church planting in the city, and would even set a national precedent, he said.

“It’s for everybody, not just us, at this stage.”