The church I was visiting in Baghdad met in the evening. When the service ended, people stood in the garden, talking as the cool air and the long twilight of the Iraqi desert settled over us.

“You should check out what’s going on upstairs,” one of the Iraqi women whispered.

I’d heard that Muslim women had begun meeting with women from the church. So I assumed I’d find about a dozen people gathered as I climbed the stairs and slowly opened the door to the upper room. To my amazement, I looked across a sea of women, row upon row, all dressed in full head-to-toe black burqas. I settled into a corner chair and scanned the room, stopping when my head count reached 350 women.

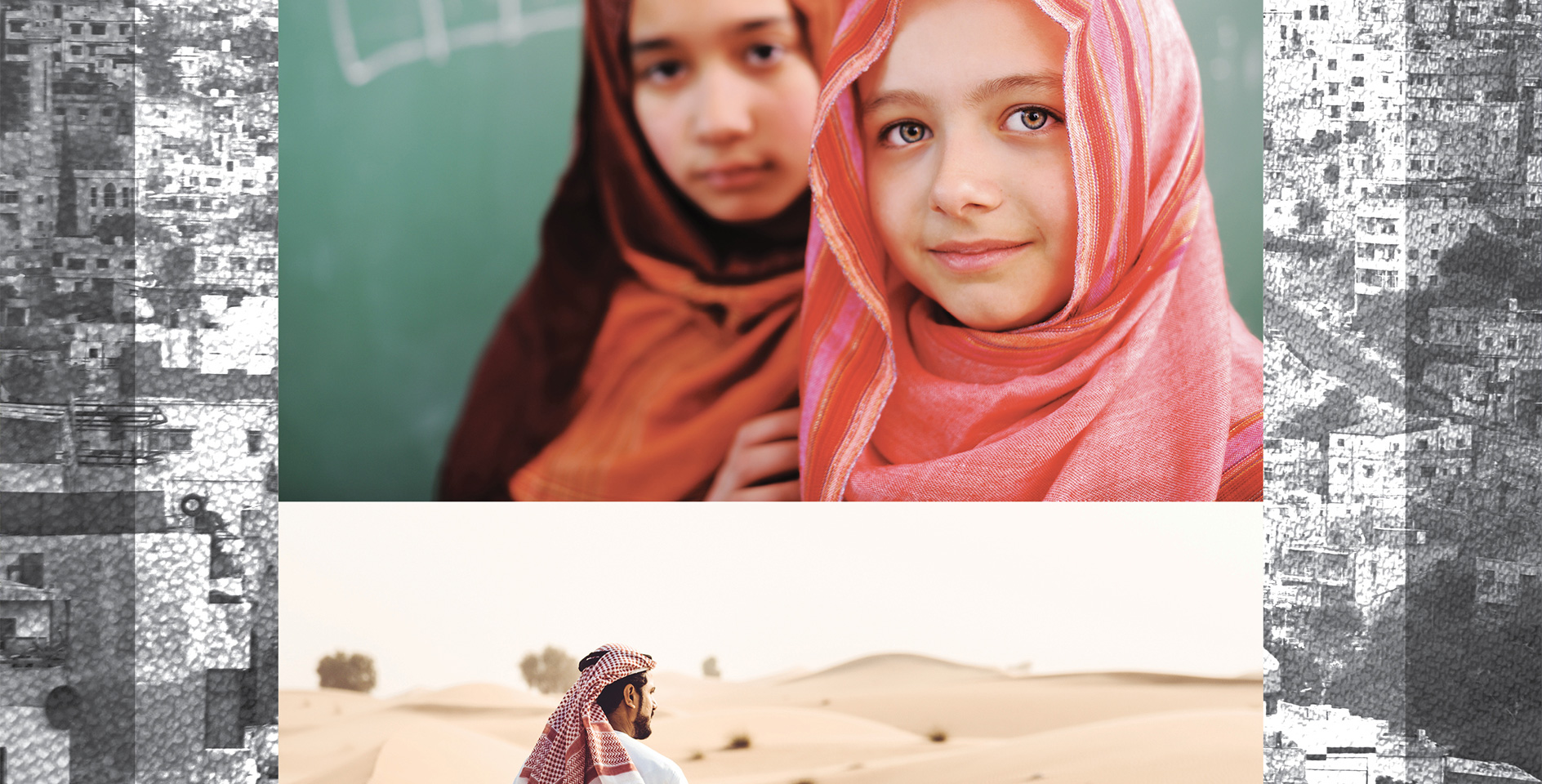

The draw of dignity

What would draw so many Shiites from some of Baghdad’s poorest neighborhoods to a church full of unveiled Christians? Christians who worshipped on the edge of the city’s Green Zone, an area full of checkpoints and government officials?

First, charity.

Months before the meetings began, the church started handing out food parcels, bringing in the Shia families from nearby neighborhoods by bus several times a month.

Second, dignity.

As women in the church got to know these Muslim women, they found that they had things in common among all their differences. This happened as Islamic State militants were taking over large areas of Iraq, spreading fear and occupying cities only 50 miles from Baghdad. ISIS, a Sunni movement, targeted not only Christians but Shia families too. Like the Christians, these Muslim women feared the future and what it held for their children.

So the women in the church invited them for conversations and to share their stories. First a few came, then 50, then the hundreds I saw. The pastor’s wife led the evening discussions—about what it means to be a Christian, about how Christian and Muslim women can help one another, caring for their children, making ends meet, and bearing burdens.

Yes, the Muslim women heard Scripture passages, but what first permeated this upper room was mutual respect, punctuated by laughter, and singing. And all of it in a room of open windows, with soldiers in the streets below. These women became fearless in the presence of one another, drawing strength from their shared humanity.

Why does human dignity survive in the dark?

I have learned the most about human dignity from seeing it under assault, yet rising up, in the midst of widespread indignity.

The Middle East Christians, living as they have for centuries under Muslim dominance, know the terrain well. At the height of the war in Syria, Chaldean Bishop Antoine Audo spoke to me by phone. It was winter, and the lights were out in his hometown of Aleppo. The phone line disconnected six times as we talked. Despite wartime hardships, he continued to hold services, to perform baptisms, and to go about the city delivering supplies to the needy. I asked how he could carry on.

“The anarchy of the war allows you to perceive in even stronger terms the greatness of human dignity, just when it seems so humiliated,” he said.

Why does human dignity survive in the darkest hellholes? Because it is an unconquerable thing. Unconquerable because it begins not with humans but with God who made them.

At the very beginning, in the garden, men and women were created in God’s image—the imago Dei. Over and over, the Old Testament histories tell us: man’s inhumanity to man cannot stop God’s devotion to man. It’s not because man is so great but because the God who made him is.

And in the last days, our days, God pours out his spirit on all flesh, says the prophet Joel, male and female, slave and free, young and old (Joe 2:28-29). The Book of Acts opens at Pentecost with this vision and these words from Joel. What God had done for Peter, writes theologian N. T. Wright, he was beginning to do for the whole world.

The stoning of Stephen tested the newfound dignity for the early believers, and a remarkable thing happened: heaven itself opens to Stephen as he is dying. He sees the glory of God and Jesus standing at God’s right hand. It’s an indelible picture for those facing persecution through the centuries—Jesus at attention over the death of his saint, and Stephen, fully aware of both his present and his future, crying, “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit.”

God plants these visions in human hearts when dignity is under assault. The ISIS militants at the height of their power knew how to debase their sworn enemies, how to make them appear less than human. They raped and sold women, they paraded kidnapped men in orange jumpsuits and then beheaded them.

Yet when the Islamic State fighters paraded 21 Egyptians before a camera in 2015, made them kneel for execution on a Libyan beach, the men in jumpsuits remained calm. Instead of protests, they gazed to heaven in prayer, whispering, “Ya Rabbi Yasou,” “My Lord Jesus.”

Maintaining dignity amid everyday indignities

For the survivors there are everyday indignities, too. The work of terrorists isn’t the only dehumanizing factor. Refugee or displacement camps meant for temporary shelter can steal dignity, too, as men and women who once owned businesses and made their own livings suddenly must subsist in tents waiting for outside help.

During that time my Iraqi friend, Insaf Safou, made it her ministry to restore everyday self-worth for women made homeless and abused by ISIS.

“Daesh [the Arabic word for ISIS] destroyed our culture, our churches, and our lives. But women have life-giving power within them, and Daesh cannot destroy the God who made us; they cannot kill our God-given dignity.”

Insaf, a former refugee herself, knew the importance of restoring what ISIS had shattered for women in Iraq and Syria. “They need to build their dignity as much as feed their families,” she said.

She believed in small projects, and that small projects would grow into larger community efforts. Once a tailor in Baghdad, she helped women with simple sewing projects. When mastered, these could help them grow businesses, sewing to support their own families, then to employ and pay other women, and in that way support whole communities.

Today Insaf’s daughter runs one such business in Iraq, Hopeful Hands. It employs Syrian and Iraqi women, Muslims and Christians, in a growing sewing cooperative. They make sheet sets and other home furnishings, and recently completed an order of graduation gowns for a local university.

For those who’ve lost their homes and most of their possessions, such work gives them more than income. It gives them routine and a sense of purpose. They learn to pray and care for one another, too.

The future of human dignity is always up for grabs, and at the same time always assured, not on what man does but on what God did, forming us from dust into his very image and spreading the love of Jesus abroad in human hearts.