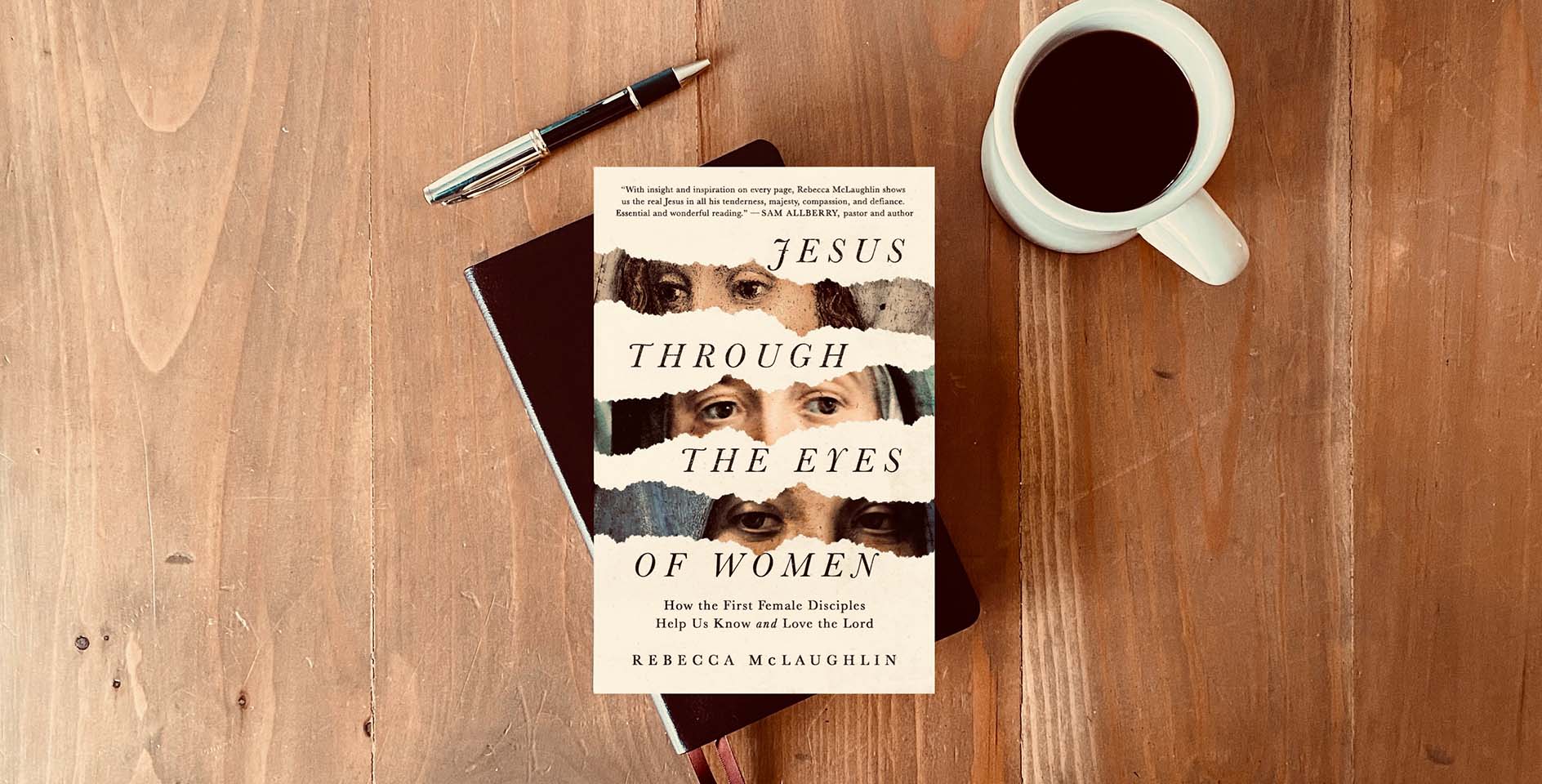

My personal study of the Scriptures has been enriched by wondering, “What was that really like?” This question feels particularly relevant to the stories of those who came face-to-face with the God-man, Jesus Christ, and lived to tell about it in the Gospels. Author Rebecca McLaughlin gives full treatment to this sort of curiosity in her book Jesus Through the Eyes of Women: How the First Female Disciples Help Us Know and Love the Lord (The Gospel Coalition, 2022).

Before we get into her masterful debunking of certain myths and stereotypes, let me deflate one on the author’s behalf: though women are in the title, this book is not just for women, and it is not even really about women. This is a book about the person of Christ, and it is for all those who want to know and follow him more. The fresh perspective it offers us is an aide to that lifelong endeavor.

The book is also for those who are questioning—or even deeply skeptical—about Jesus and about the Bible that tells of his improbable life, death, and resurrection. McLaughlin has spent plenty of time considering the cynic’s vantage point, with books that include Confronting Christianity: 12 Hard Questions for the World’s Largest Religion in 2020 and The Secular Creed: Engaging 5 Contemporary Claims in 2021. She effortlessly brings them along in this project as well.

Birthed out of McLaughlin’s own inquisitiveness, Jesus Through the Eyes of Women was written at “breakneck speed” in late 2021, said Ivan Mesa, TGC’s editorial director. It reads easily, too, as if penned in nearly one sitting. Though there is plenty to underline in a print edition, the author’s British accent makes the just over 4-hour audiobook a delightful option as well.

A winsome apologist with a Ph.D. in renaissance literature and a degree in theology, McLaughlin brings an academic’s understanding of history, context, and biblical commentary to bear on the core question of this book: How did the women named in the Bible describe their interactions with a Christ who was as countercultural then as he is today? And what would we have missed had these women not told others, ‘I have seen the Lord’? (John 20:18)

“To look at Jesus through the eyes of women may seem at first like an innately modern project,” McLaughlin admits in the book’s conclusion. But “what we see through their eyes is not an alternative Jesus, but rather the authentic Jesus, who welcomes both men and women as his disciples, and who is best seen from below.”

Though she leads into the subject with mention of the Gnostic Gospel of Mary (a text from the early church period rejected as heretical), acknowledging why it would resonate with some who view the Bible as dismissive of women—don’t worry. McLaughlin’s thesis is that the first-century Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John already reflect the eyewitness testimony of women who met Jesus and that “the Jesus we see through their eyes is more beautiful, more historically accurate, and more valuing of women than anything the Gospel of Mary can offer.”

McLaughlin’s even-handed approach would make the book a viable suggestion even for a secular book club, and questions written by TGC’s Joanna Kimbrel at the end of each chapter make such discussions even easier. Have a few academics or self-declared feminists in the group? All the better. These are the types of readers McLaughlin seems eager to bring along, graciously refuting some of the false claims they may have heard about Christianity—that it is, at best, dismissive of the female experience and, at worst, harmful to women—while introducing them to the one who “valued women of all kinds—especially those vilified by others.”

But those who would avoid the book for fear it is tainted by feminist underpinnings would do well to pick it up, too. McLaughlin is faithful to the biblical text and to history while being keenly aware of our current cultural moment. Rather, this book lands in the good company of Dane Ortlund’s Gentle and Lowly and Paul E. Miller’s J-Curve through its meditation on Christ’s momentum toward the lowly and its call that we respond.

After building inroads for a variety of readers, McLaughlin gets into the nitty-gritty details of how women’s accounts added to the picture we see the Gospels paint of Jesus. Which stories in these books were likely included only because women witnessed and relayed them? It turns out, plenty. “If we cut the things that only women witnessed, we’d lose our first glimpse of Jesus as he took on human flesh and our first glimpse of his resurrected body,” McLaughlin writes. “The four Gospels preserve the eyewitness testimony of women.”

The book delves into what these women witnessed by dividing the stories into six broad categories, from discipleship and nourishment, to healing and forgiveness.

Zooming in

Asking what Jesus looked like through their eyes helps us relate in fresh ways to familiar female characters like his mother, Mary. Just as the prophecy that new life is being birthed inside her seems unfathomable when it first arrives, the Christian can also wonder just how the promised newness of life in Christ is really at work in him or her. “Through Mary’s eyes, we see the life-upending blessing of receiving Jesus,” McLaughlin summarizes.

The book introduces us to lesser-known women of the Bible, too, like Joanna, the wife of Herod’s household manager and a likely source of inside information from the halls of power (Luke 9:1-3; 9:9). In his Gospel account, Luke would have named Joanna and other women who were with Jesus “in order to flag them as eyewitness sources” for some of the stories he includes, McLaughlin writes. McLaughlin also revisits biblical women we think we know, from Mary Magdalene to Lazarus’ sisters.

Perhaps my favorite of these is the author’s take on the well-known story of Mary and Martha. When Jesus tells Martha, who is “distracted with much serving,” that her sister Mary “has chosen the good portion” by sitting at his feet, McLaughlin doesn’t see it as an indictment of the domestic anxieties that can plague women (how often have you heard a woman confess to “being a Martha”?). Rather, his words are a “validation of female discipleship,” of Mary’s and Martha’s access to Jesus as thinkers and students, not just servers.

Through the eyes of these sisters, “we see [Jesus] as the one who welcomes women and defends their right to learn from him. We also see him as the one who gives us so much more than we could ever give to him.”

It’s paradigm-shifting, then, to consider that this Martha is the one to whom Jesus later speaks some of his “most world-transforming” words: “I am the resurrection and the life.” McLaughlin points out that almost all of Jesus’ ‘I am’ statements are spoken to groups, but the two that are spoken to individuals are spoken to women.

Besides John, women are largely the consistent witnesses of Jesus’ excruciating death, burial, and resurrection as well. In a chapter on life, McLaughlin focuses on these women’s accounts to winsomely argue for, not against, biblical soundness at several points, anticipating opposing views. She even quotes a resurrection skeptic and politely refutes his claims.

She reminds us that, in that culture, the only reason to say that women witnessed all this is that they really did.

Bringing Christ into focus

In her chapters on healing and forgiveness, McLaughlin acknowledges the messier stories, too. Jesus’ interaction with the bleeding woman, in particular, “shows he doesn’t shy away from femaleness.” This is often in sharp contrast to the responses of those around him. When this woman reaches for his cloak, “Jesus does not recoil.”

As he is with these women, he is also with us. “Jesus is no more put off by our inevitable uncleanness than a mother who has just given birth would be put off from holding her blood-smeared newborn. Before long, Jesus would bleed for this woman.”

Her chapter on the theme of forgiveness brings into focus Jesus’ infamous interactions with women of ill repute. These stories show a Jesus who “welcomed prostitutes: not like the other men of his day, and of ours, but like a loving brother, searching for his sister in the slums to bring her home.” Why does he welcome them? Not because of permissiveness, McLaughlin writes, but because of their repentance.

Through the eyes of the sinful woman who crashes Simon the Pharisee’s dinner party (Luke 7:36-49), at last we see Jesus as “the one who defends” the woman wetting his feet with her tears and wiping them with her hair. Rather than tearing this woman down along with his host, Jesus lifts her up “as a shining, tear-stained paragon of love to humble the self-righteous Pharisee.”

All this goes to show that those who throw themselves at Christ’s feet are the ones who will enter his kingdom. In this way, Jesus Through the Eyes of Women bridges the growing gap between how cultures—both the New Testament’s and our own—treat women who equally bear God’s image, and how the Jesus of the Bible did. We would do well to ingest, imitate, and marvel at the latter.