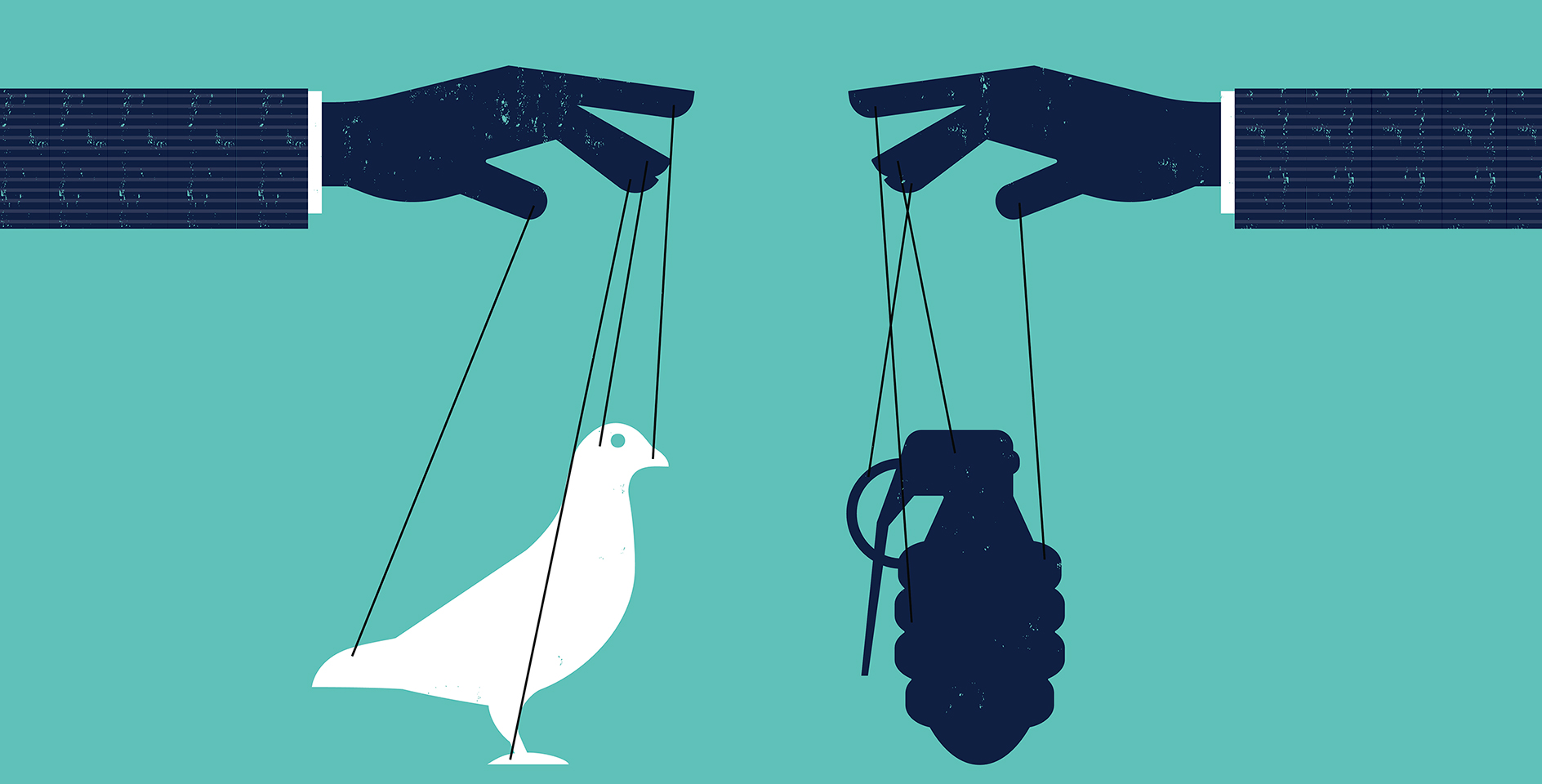

What are the moral reasons for going to war? What does justice require of us when engaging in warfare? What are our ethical obligations to our enemy once warfare has ceased?

The attempt to answer these questions has led to the development of just war theory and the just war tradition. The theoretical aspect of military ethics concerned with morally justifying war and the forms that warfare may or may not take is called just war theory. The history of just war thought and its application to specific wars is referred to as the just war tradition. The Christian just war tradition is therefore the history of how just war theory has been conceived and applied in Christian thought and ethics. (Hereafter, “JWT” will refer to the Christian just war tradition.)

In this five part series on the Christian just war tradition we’ll examine the three main areas of just war theory: jus ad bellum (the moral requirement for going to war), jus in bello (the moral requirements for waging war), and jus post bellum (moral requirements after warfare is concluded). We’ll also look at how the just war tradition applies to terrorism and the use of nuclear weapons.

The Biblical and Christian Roots of the Just War Tradition

The Christian tradition of just war theory began in the fifth century with Augustine. Augustine’s view of justice in warfare can be summed up by his statement that, “We do not seek peace in order to be at war, but we go to war that we may have peace. Be peaceful, therefore, in warring, so that you may vanquish those whom you war against, and bring them to the prosperity of peace.”

In the thirteenth century, Thomas Aquinas built on and expanded Augustine’s thought on justice and warfare. Later Christian thinkers have added nuance and commentary on the JWT, but the main principles we still use today are those derived from Augustine and Aquinas.

The JWT of Augustine and Aquinas is rooted in Romans 13:3-4: “For rulers are not a terror to good conduct, but to bad. Do you want to be unafraid of the authority? Do what is good, and you will have its approval. For it is God’s servant for your good. But if you do wrong, be afraid, because it does not carry the sword for no reason. For it is God’s servant, an avenger that brings wrath on the one who does wrong.” As Marc LiVecche explains,

Paul’s emphasis on the good of government helps signal the just war tradition as essentially eudaemonist – that is, it promotes genuine human flourishing. It accomplishes this through fidelity to the fundamental Christian duty of neighbor love. This principle norm makes a universal anthropological assertion: All human beings, including our enemies, are right objects of love. This is because in the biblical view every human individual is made in the image of God and has a particular call to exercise dominion and participate in the care, and salvation, of the world. From this universal assertion that every human being enjoys equal dignity there issues a consequent universal command: All human beings are to love every other.

The way in which just war promotes the love and flourishing of the neighbor under assault should be quite clear. In order to flourish through properly responding to our created call, human beings need to enjoy those goods which make any such response possible. Most basically, of course, this includes the good of life. Because of this, the primary good for which government exercises responsibility is the provision of basic security characterized by order, justice, and peace without which no degree of human flourishing, including life, can long persevere.

As LiVecche notes, these goods correspond directly to the conditions necessary for a just resort to force.

The Principles of Jus ad Bellum

There are six criteria that must be satisfied before entering war can be considered just:

1. Just Cause – There must be a just and proper reason for going to war. Some of the justifiable reasons include self-defense, protecting the innocent (e.g., preventing genocide), restoring human rights wrongly denied, and assisting an ally in their self-defense.

2. Proportionate Cause – The good of going to war must outweigh the destruction and death that will be caused by warfare. In other words, going to war must prevent more evil and suffering than it is expected to cause.

3. Right Intention – Our reasons and motives for engaging in warfare must noble and in line with the ethic of Christian love. We can go to war to right a wrong or restore a just peace but not to restore our “national pride” or to seek revenge against an enemy.

4. Right Authority – War can only be authorized by a legitimate governing authority. This means it has to be a governing authority we would recognize as fitting the criteria of Romans 13. But it also means that the proper governing authority has actual sovereign authorization to engage in war. For example, the President of the United States has the proper authority to initiate warfare against Canada while the governor of North Dakota does not.

5. Reasonable Chance of Success – The initiation of warfare brings violence, pain, and suffering. This cost is only worth paying if it will, as we noted, outweigh the destruction and death that will be caused by warfare. If there is no reasonable chance of success in warfare there can be no reasonable chance of using warfare to restore a just peace.

6. Last Resort – Engaging in warfare must be the last reasonable and workable option for addressing problems. Any peaceful alternatives, such as diplomacy or non-violent political pressure, must first be exhausted before going to war.

All of these criteria must be met before a nation can be justified in going to war. However, because these criteria are open-ended and subject to interpretation, it is often a matter of contention among Christians about whether the standard has been satisfied before war has been declared or entered into. For example, there has been no war in American history in which Christians did not disagree about whether it met the standard of the just war tradition.

Next in the Series: In our next article, we’ll look at the criteria for justly engaging in warfare.