What just happened?

Recent protests centered around racial injustice and the killing of African American, like George Floyd and many others, have led to a renewed debate over the meaning and significance of historical monuments. Over the past three weeks, over 100 monuments across the United States have been torn down or scheduled for removal.

Which monuments are involved?

The removal efforts fall into two broad categories. The first category includes the use of legal and legislative means of removing statuary, and has focused primarily on Civil War-era figures (such as Confederate generals and the Emancipation Statue in Washington, D.C.) and Christopher Columbus (19 memorials to the Italian explorer have been removed so far).

The second category includes the vandalism or use of illegal means to remove memorials, often done spontaneously as part of protests. The targets of these efforts have been more haphazard and include anti-slavery activists, feminist iconography, and Christian missionaries.

Why are Confederate statues the primary focus?

In 2015, Dylann Roof murdered nine Black congregants at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. That mass shooting sparked renewed efforts—both legal and illegal—to remove Confederate memorials around the country. For example, the New Orleans’s city council voted to remove the city’s four Confederate monuments, and in Durham, North Carolina, protestors smashed a statue of a Confederate soldier that stood outside the county’s courthouse.

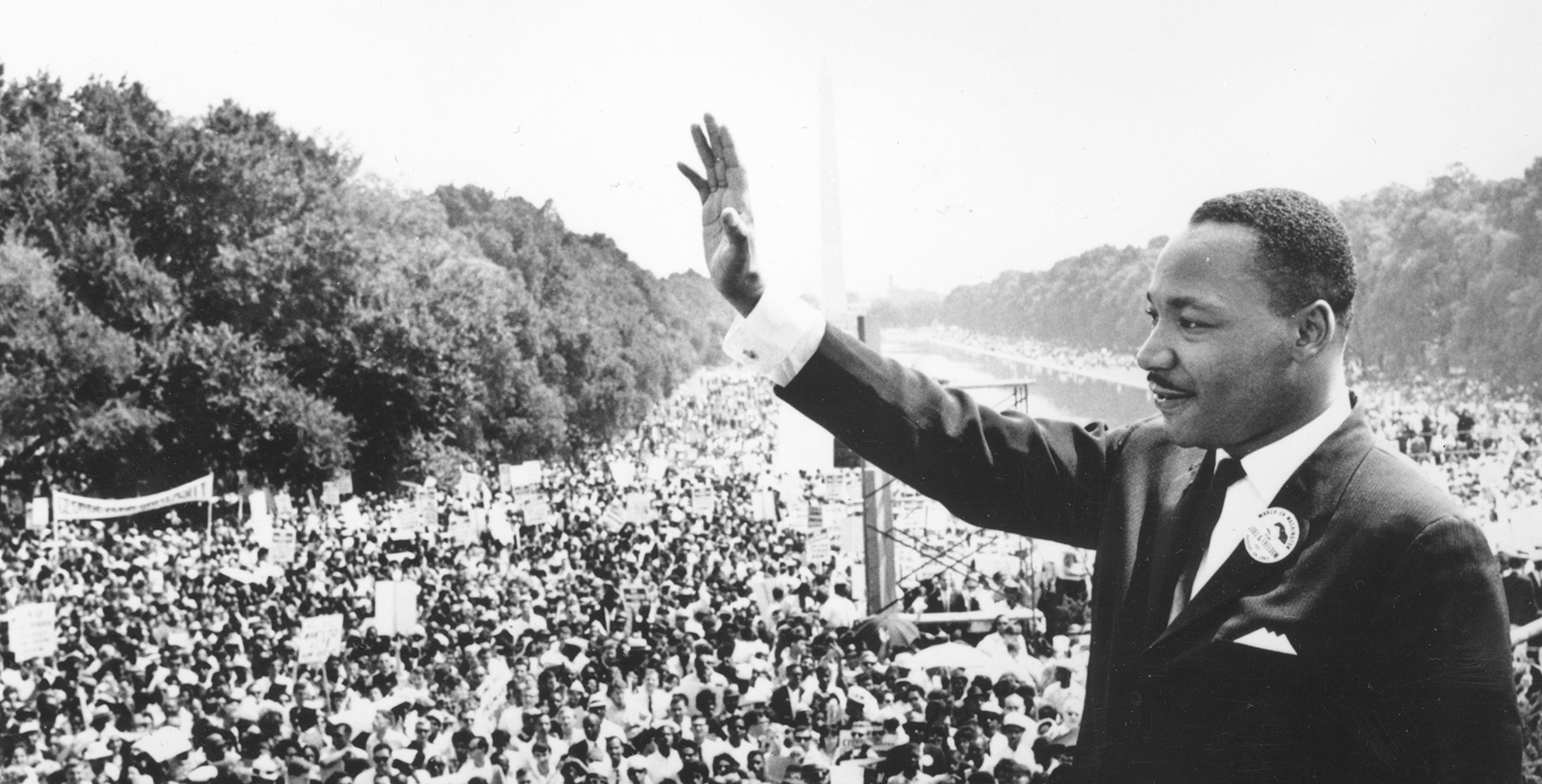

These statues have mainly been focused upon because of their connection to white supremacy and racial injustice. The majority of Confederate monuments were erected in the immediate aftermath of the Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), when many state laws began reestablishing racial segregation, and from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s, during the peak of the civil rights movement. As David A. Graham says, “In other words, the erection of Confederate monuments has been a way to perform cultural resistance to black equality.”

What prevents the illegal removal of monuments?

The Veterans’ Memorial Preservation and Recognition Act of 2003, makes it a federal crime to willfully injure or destroy, or attempt to injure or destroy, any “structure, plaque, statue, or other monument on public property commemorating the service of any person or persons in the armed forces of the United States.” Similarly, vandalism and destruction of monuments on federal property is also already a federal crime.

To enforce the laws, about 400 unarmed D.C. National Guardsmen were put on standby at the Washington, D.C. Armory to provide backup to National Park Police to help prevent damage at key monuments in the city. An email has also been sent to U.S. marshals notifying them that they should prepare to help protect national monuments. Marshals Service Assistant Director Andrew C. Smith wrote that the agency “has been asked to immediately prepare to provide federal law enforcement support to protect national monuments (throughout the country).”

Why do we not immediately remove all controversial monuments?

The process of removing public monuments is often hindered by legal restrictions. Public monuments are protected by an interlocking web of international-, federal-, and state-level law intended to protect cultural property. As E. Perot Bissell V notes in the Yale Law Journal, modern cultural-property law emerged in the wake of the destruction and looting that followed World War II. “Because cultural-property law’s original purpose was to address the potential for wartime destruction of the world’s Treasures,” says Bissell, “its organizing principle is the preservation of historically or aesthetically significant heritage.”

Since cultural-property law developed in response to widely deplored acts of destruction, it is focused on preservation of existing monuments. This can make it difficult to remove statues and memorials even when the society’s values have changed and the subject is no longer considered worthy of honor.

Take, for example, the Nathan Bedford Forrest Monument, which was removed from a park in Memphis, Tennessee, in 2017. The monument to the founder of the Ku Klux Klan was protected by the 1954 Hague Convention, the Veterans’ Memorial Preservation and Recognition Act of 2003, and a state law forbidding the removal of any statue from state property. According to Bissell, “Memphis ultimately removed its Forrest Monument through a clever work-around, transferring the park in which it stood to a nonprofit.”

How should Christians think about the removal of monuments?

A useful starting point might be to consider the historical circumstances of the monument’s erection and determine whether the motivation or cause for remembrance is a value that a Christian would consider worthy of memorializing.

For example, Confederate statues are obvious candidates for removal from public spaces, since their purpose is to venerate a cause that celebrated slavery, segregationism, and white supremacy. In contrast, monuments related to the Founding Fathers were not typically erected to remember their accomplishments as slave-holders, but for their more noble accomplishments.

The context and location of the monument should also be given consideration. Christians might ask if this exact monument didn’t exist, how likely is it that we would support making a new monument to this person in this way at this location?

For example, Speaker Nancy Pelosi recently called for the removal of 11 Confederate statues from the U.S. Capitol. Two of the statues include Jefferson Davis and Alexander Stephens, the president and vice president of the Confederate States of America. Whatever else we might think about remembrances of the Confederacy, it seems unlikely that we’d choose today to honor traitors to our nation in the halls of our legislature.

Monuments are more than mere historical reminders. They become part of our historical memory, showing what we think is worthy of being honored and revered. As we become more honest with ourselves as a nation about the darker areas of our history, we should consider what is worth celebrating. As Christians, we are called to “do all to the glory of God” (1 Cor. 10:31), which might require rethinking how we memorialize our past.