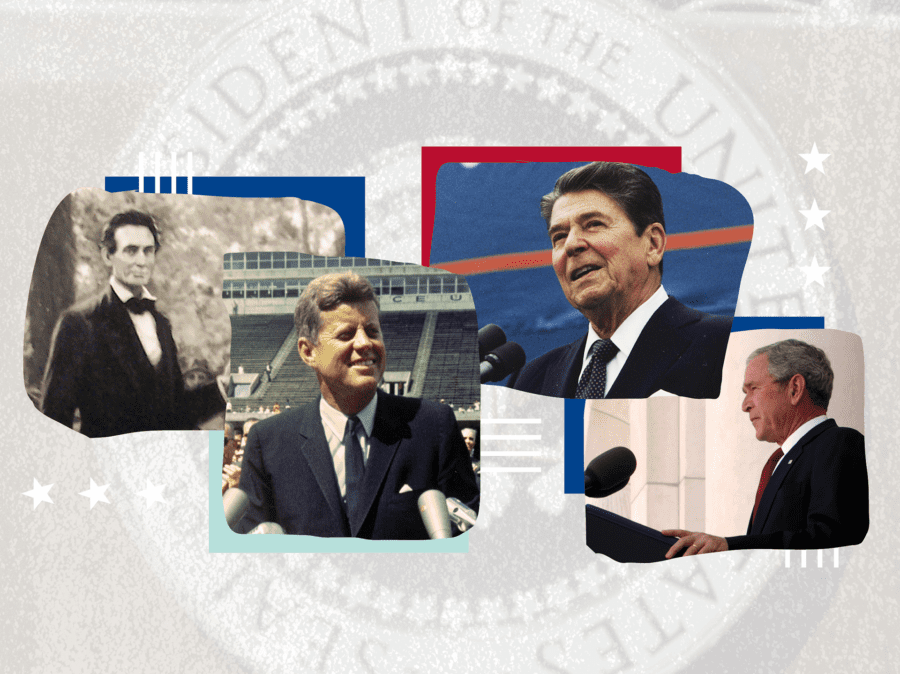

Historically, noteworthy presidential rhetoric has often been in response to extenuating circumstances. President Abraham Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address,” given during the deadly Civil War, is one of the most quoted speeches given by an American president in our nation’s history, remembered in its entirety. And following 9/11, President George W. Bush asserted, “Terrorist attacks can shake the foundations of our biggest buildings, but they cannot touch the foundation of America. These acts shattered steel, but they cannot dent the steel of American resolve.”

Presidential rhetoric can also serve to summarize a key political position. One of President Ronald Reagan’s most quoted statements comes from a press conference in 1986 where he declared, “… the nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I’m from the Government, and I’m here to help.” By including this line, Reagan expertly pointed to a large part of his platform: deregulation and lowered government spending.

Similarly, President John F. Kennedy is quoted from his inaugural address in which he proclaimed, “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.” This rallying cry for self-sacrifice tied in to Kennedy’s New Frontier platform, which emphasized a federal space program and the eradication of poverty through the expansion of federal programs.

Shifting presidential rhetoric

Over the past few decades, though, presidential rhetoric has shifted from a reflection of local and national discourse and of party platforms to an individualistic exercise. Instead of vying for voter support, candidates compete for air time with viral messaging on news programming and social media. Our expectations for presidential rhetoric are increasingly substandard; we accept less cohesive statements and more short, snappy sound bites easily taken out of context and easier still to digest.

We see this reflected through new norms, where it’s common for legislators and officials to post policy positions on X, create memes designed solely to go viral, stir up conflict in committee meetings to gain notoriety for an upcoming reelection campaign, and repeatedly apply labels to the “other side.” This rhetoric rejoices not in persuading undecided voters or being accountable for the treatment of our fellow man but delights in criticizing someone who is both unlike and unlikable to us.

Characteristics of good presidential rhetoric

As Christians, we hold that our words carry weight as more than just a messaging tool. They function like a rudder of a ship or a bit in a horse’s mouth, leading the person who speaks them and forging a path for constituents to follow (James 3). This raises an important question: what is considered good presidential rhetoric?

Good presidential rhetoric is forgettable.

It does not seek acclaim or applause. It does not issue a rallying cry where it is unwarranted or seek to encourage impassioned devotion toward the president himself. Simply put, good presidential rhetoric is merely focused on the undistinguished, day-to-day act of responsible governance.

Good presidential rhetoric unifies.

It positions the United States as a nation of we—where our identity is not found in our political party, but in our citizenship. Healthy presidential rhetoric knows that our elected officials represent and serve all constituents, including those that voted in opposition, and is willing to disagree with constituents in order to seek their best interest.

Good presidential rhetoric holds constituents to a higher standard.

A common attitude in politics today is that individual voters are smart, but collective voters are unintelligent or uninformed. While this is usually stated in response to illogical voting patterns, what this phrase actually does is treat constituents as infants to be guided and manipulated. In reality, voters should be compelled to rise to the standard of informed voting as capable adults who are able to digest policies and political realities. Good rhetoric responds by presenting voters with digestible and accurately represented policy platforms.

Good presidential rhetoric does not hold a presidential candidate before constituents as a salvific figure to be beheld, but as an official to be elected.

A wise candidate will not claim a nation’s future hinges upon his or her election to public office. Similarly, as Christians, we know our only Savior is found in Christ, and any elected official will inevitably fail us. However, this reality does not recuse us from our moral obligation to think deeply about our nation and its leaders. The hard, meaningful work for believers is found in the in-between—not just in how we vote, but in the process leading up to and following political engagement.

What will we choose?

So, will we be people who value rhetoric held to a high standard? Will we have the courage to seek kindness and conviction in word and speech? Or will we find temporary satisfaction in words without restraint?

The political reality remains that presidential candidates are increasingly incentivized against meeting these standards because voters and donors alike often turn out for radicalizing language, whether or not it is true. And yet, we know that negativity is not necessarily realism, and hope is not naive. We, as voters, incentivize them to behave this way. If we can change our expectations of elected officials, we are not resigned indefinitely to candidates whose speech is harmful, whether this is glorifying the murder of a preborn child through abortion or intentionally lashing out against that child’s mother.

Both as believers and as Americans, we must strive to hold on to a biblical vision of beauty in governance.

We should seek leaders whose rhetoric brings order where there is chaos in both word and deed. This, in turn, seeks the good of neighbor over the good of self and enables us to cling to the redemptive truth of the gospel, both for ourselves and for the officials we vote for in the ballot box. The very truth of the gospel that we proclaim in our own speech compels us to do so.