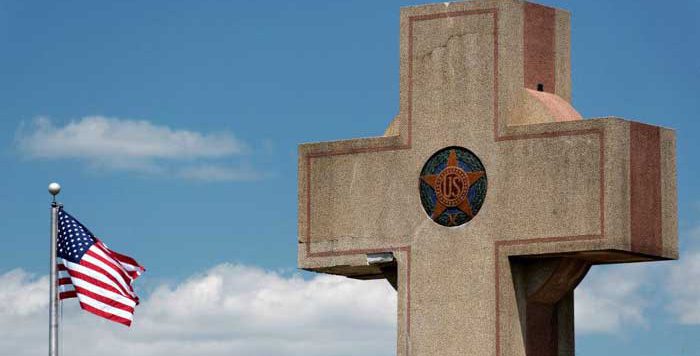

The Supreme Court ruled today on American Legion v. American Humanist Association, a case in which the justices considered whether or not the display of a World War I memorial cross standing on government owned property in Bladensburg, Maryland violates the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. With a 7-2 decision, the Court upheld the constitutionality of this Bladensburg Cross memorial.

Jeremy Dys, Deputy General Counsel for First Liberty, wrote an article for ERLC ahead of the case’s oral argument which tells the story at the heart of this case. Dys writes, “On July 12, 1925, The American Legion erected the Bladensburg World War I Veterans Memorial, fulfilling the vision Gold Star mothers announced in 1919 as a way to honor 49 of their sons who died in World War I. The Memorial stood peacefully for nearly a century, until the American Humanist Association (“AHA”) filed a lawsuit alleging the cross-shaped monument violated the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause. Their lawsuit demands that the memorial be removed, altered, or demolished. In late 2017, the U.S Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit agreed with AHA. First Liberty and attorneys at the international law firm Jones Day, representing The American Legion, appealed.”

The ERLC filed an amicus brief in support of the petitioners, arguing that the cross is not an “establishment of religion.” The brief also argued in favor of a judicial test that would both confirm historical practices and uphold religious liberty.

While the decision to uphold this memorial garnered the votes of seven justices, the Court’s opinion is split into multiple parts and multiple opinions. Justice Alito authored the Majority opinion, though Justices Kagan, Breyer, Kavanaugh, Thomas, and Gorsuch each wrote concurrences, and Justice Ginsburg authored the lone dissent. Chief Justice Roberts concurred with the majority and Justice Sotomayor concurred with the dissent.

Below are key quotes from these opinions highlighting how the Supreme Court reached its decision. Page numbers from the Court’s decision are given for each quote, but legal citations are omitted for clarity of reading.

Alito, majority opinion in multiple parts with various justices joining

Intro

“[T]he Bladensburg memorial… has become a prominent community landmark, and its removal or radical alteration at this date would be seen by many not as a neutral act but as the manifestation of a hostility toward religion that has no place in our Establishment Clause traditions…” (2)

“The Religion Clauses of the Constitution aim to foster a society in which people of all beliefs can live together harmoniously, and the presence of the Bladensburg Cross on the land where it has stood for so many years is fully consistent with that aim.” (2)

PART II-A – Plurality Opinion authored by Alito, joined by Roberts, Breyer, and Kavanaugh

“[T]he Lemon test presents particularly daunting problems in cases, including the one now before us, that involve the use, for ceremonial, celebratory, or commemorative purposes, of words or symbols with religious associations. Together, these considerations counsel against efforts to evaluate such cases under Lemon and toward application of a presumption of constitutionality for long standing monuments, symbols, and practices.” (15–16, emphasis added)

PART II-B – Majority Opinion authored by Alito, joined by Roberts, Breyer, Kagan, and Kavanaugh

“As our society becomes more and more religiously diverse, a community may preserve such monuments, symbols, and practices for the sake of their historical significance or their place in a common cultural heritage.” (18)

“For at least four reasons, the Lemon test presents particularly daunting problems in cases, including the one now before us, that involve the use, for ceremonial, celebratory, or commemorative purposes, of words or symbols with religious associations.” (15)

“First, these cases often concern monuments, symbols, or practices that were first established long ago, and in such cases, identifying their original purpose or purposes may be especially difficult.” (16)

“Second, as time goes by, the purposes associated with an established monument, symbol, or practice often multiply.” (17)

“Third, just as the purpose for maintaining a monument, symbol, or practice may evolve, “[t]he ‘message’ conveyed . . . may change over time.” (19)

“Fourth, when time’s passage imbues a religiously expressive monument, symbol, or practice with this kind of familiarity and historical significance, removing it may no longer appear neutral, especially to the local community for which it has taken on particular meaning. A government that roams the land, tearing down monuments with religious symbolism and scrubbing away any reference to the divine will strike many as aggressively hostile to religion. Militantly secular regimes have carried out such projects in the past, and for those with a knowledge of history, the image of monuments being taken down will be evocative, disturbing, and divisive.” (20)

“These four considerations show that retaining established, religiously expressive monuments, symbols, and practices is quite different from erecting or adopting new ones. The passage of time gives rise to a strong presumption of constitutionality.” (21)

PART II-C – Majority Opinion authored by Alito, joined by Roberts, Breyer, Kagan, and Kavanaugh

“This is not to say that the cross’s association with the war was the sole or dominant motivation for the inclusion of the symbol in every World War I memorial that features it. But today, it is all but impossible to tell whether that was so. The passage of time means that testimony from those actually involved in the decision making process is generally unavailable, and attempting to uncover their motivations invites rampant speculation. And no matter what the original purposes for the erection of a monument, a community may wish to preserve it for very different reasons, such as the historic preservation and traffic- safety concerns the Commission has pressed here.” (22)

Part II-D – Plurality Opinion authored by Alito, joined by Roberts, Breyer, and Kavanaugh

“While the Lemon Court ambitiously attempted to find a grand unified theory of the Establishment Clause, in later cases, we have taken a more modest approach that focuses on the particular issue at hand and looks to history for guidance.” (24–25)

“The practice begun by the First Congress stands out as an example of respect and tolerance for differing views, an honest endeavor to achieve inclusivity and nondiscrimination, and a recognition of the important role that religion plays in the lives of many Americans. Where categories of monuments, symbols, and practices with a longstanding history follow in that tradition, they are likewise constitutional.” (28)

Part III – Majority Opinion authored by Alito, joined by Roberts, Breyer, Kagan, and Kavanaugh

“As we have explained, the Bladensburg Cross carries special significance in commemorating World War I. Due in large part to the image of the simple wooden crosses that originally marked the graves of American soldiers killed in the war, the cross became a symbol of their sacrifice, and the design of the Bladensburg Cross must be understood in light of that background. That the cross originated as a Christian symbol and retains that meaning in many contexts does not change the fact that the symbol took on an added secular meaning when used in World War I memorials. Not only did the Bladensburg Cross begin with this meaning, but with the passage of time, it has acquired historical importance.” (28)

“Finally, it is surely relevant that the monument commemorates the death of particular individuals. It is natural and appropriate for those seeking to honor the deceased to invoke the symbols that signify what death meant for those who are memorialized.” (30)

Part IV – Majority Opinion, authored by Alito, joined by Roberts, Breyer, Kagan, and Kavanaugh

“The cross is undoubtedly a Christian symbol, but that fact should not blind us to everything else that the Bladensburg Cross has come to represent. For some, that monument is a symbolic resting place for ancestors who never returned home. For others, it is a place for the community to gather and honor all veterans and their sacrifices for our Nation. For others still, it is a historical landmark. For many of these people, destroying or defacing the Cross that has stood undisturbed for nearly a century would not be neutral and would not further the ideals of respect and tolerance embodied in the First Amendment. For all these reasons, the Cross does not offend the Constitution.” (31)

Breyer, concurring, joined by Kagan

“[I do not] understand the Court’s opinion today to adopt a ‘history and tradition test’ that would permit any newly constructed religious memorial on public land… The Court appropriately ‘looks to history for guidance…, but it upholds the constitutionality of the Peace Cross only after considering its particular historical context and its long-held place in the community… A newer memorial, erected under different circumstances, would not necessarily be permissible under this approach.” (2)

“The case would be different, in my view, if there were evidence that the organizers had ‘deliberately disrespected’ members of minority faiths or if the Cross had been erected only recently, rather than in the aftermath of World War I… But those are not the circumstances presented to us here, and I see no reason to order this cross torn down simply because other crosses would raise constitutional concerns.” (2)

Kavanaugh, concurring

“Today, the Court declines to apply Lemon in a case in the religious symbols and religious speech category, just as the Court declined to apply Lemon in Town of Greece v. Galloway, Van Orden v. Perry, and Marsh v. Chambers. The Court’s decision in this case again makes clear that the Lemon test does not apply to Establishment Clause cases in that category. And the Court’s decisions over the span of several decades demonstrate that the Lemon test is not good law…” (3)

“The practice of displaying religious memorials, particularly religious war memorials, on public land is not coercive and is rooted in history and tradition. The Bladensburg Cross does not violate the Establishment Clause.” (4)

“The conclusion that the cross does not violate the Establishment Clause does not necessarily mean that those who object to it have no other recourse. The Court’s ruling allows the State to maintain the cross on public land. The Court’s ruling does not require the State to maintain the cross on public land. The Maryland Legislature could enact new laws requiring removal of the cross or transfer of the land. The Maryland Governor or other state or local executive officers may have authority to do so under current Maryland law. And if not, the legislature could enact new laws to authorize such executive action. The Maryland Constitution, as interpreted by the Maryland Court of Appeals, may speak to this question. And if not, the people of Maryland can amend the State Constitution.” (5)

Kagan, concurring

“Although I agree that rigid application of the Lemon test does not solve every Establishment Clause problem, I think that test’s focus on purposes and effects is crucial in evaluating government action in this sphere—as this very suit shows.” (1)

“ … the opinion shows sensitivity to and respect for this Nation’s pluralism, and the values of neutrality and inclusion that the First Amendment demands.” (2)

Thomas, concurring in the judgment

“The Establishment Clause states that ‘Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.’ U.S. Const., Amdt. 1. The text and history of this Clause suggest that it should not be incorporated against the States. Even if the Clause expresses an individual right enforceable against the States, it is limited by its text to ‘law[s]’ enacted by a legislature, so it is unclear whether the Bladensburg Cross would implicate any incorporated right. And even if it did, this religious display does not involve the type of actual legal coercion that was a hallmark of historical establishments of religion. Therefore, the Cross is clearly constitutional.” (1)

“The Bladensburg Cross is constitutional even though the cross has religious significance as a central symbol of Christianity.” (4)

“As to the long-discredited test set forth in Lemon v. Kurtzman, . . . the plurality rightly rejects its relevance to claims, like this one, involving ‘religious references or imagery in public monuments, symbols, mottos, displays, and ceremonies.’ I agree with that aspect of its opinion. I would take the logical next step and overrule the Lemon test in all contexts. First, that test has no basis in the original meaning of the Constitution. Second, ‘since its inception,’ it has ‘been manipulated to fit whatever result the Court aimed to achieve. . . . Third, it continues to cause enormous confusion in the States and the lower courts. . . . In recent decades, the Court has tellingly refused to apply Lemon in the very cases where it purports to be most useful…. The obvious explanation is that Lemon does not provide a sound basis for judging Establishment Clause claims.’ However, the court below ‘s[aw] fit to apply Lemon’ . . . . It is our job to say what the law is, and because the Lemon test is not good law, we ought to say so. Regrettably, I cannot join the Court’s opinion because it does not adequately clarify the appropriate standard for Establishment Clause cases. Therefore, I concur only in the judgment.” (6)

Gorsuch, concurring in judgment, joined by Thomas

“This ‘offended observer’ theory of standing has no basis in law. Federal courts may decide only those cases and controversies that the Constitution and Congress have authorized them to hear.” (2)

“It’s not hard to see why this Court has refused suits like these. If individuals and groups could invoke the authority of a federal court to forbid what they dislike for no more reason than they dislike it, we would risk exceeding the judiciary’s limited constitutional mandate and infringing on powers committed to other branches of government. Courts would start to look more like legislatures, respond- ing to social pressures rather than remedying concrete harms, in the process supplanting the right of the people and their elected representatives to govern themselves.” (3)

“As today’s plurality rightly indicates in Part II–A, however, Lemon was a misadventure. It sought a ‘grand unified theory’ of the Establishment Clause but left us only a mess.” (7)

“Though the plurality does not say so in as many words, the message for our lower court colleagues seems unmistakable: Whether a monument, symbol, or practice is old or new, apply Town of Greece, not Lemon.” (9)

“Abandoning offended observer standing will mean only a return to the usual demands of Article III, requiring a real controversy with real impact on real persons to make a federal case out of it. Along the way, this will bring with it the welcome side effect of rescuing the federal judiciary from the sordid business of having to pass aesthetic judgment, one by one, on every public display in this country for its perceived capacity to give offense.” (10)

Ginsburg, dissent, joined by Sotomayor

“Decades ago, this Court recognized that the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the Constitution demands governmental neutrality among religious faiths, and between religion and nonreligion. . . . Today the Court erodes that neutrality commitment, diminishing precedent designed to preserve individual liberty and civic harmony in favor of a “presumption of constitutionality for long standing monuments, symbols, and practices.” (2)

“Just as a Star of David is not suitable to honor Christians who died serving their country, so a cross is not suitable to honor those of other faiths who died defending their nation. Soldiers of all faiths ‘are united by their love of country, but they are not united by the cross.’” (3)

“By maintaining the Peace Cross on a public highway, the Commission elevates Christianity over other faiths, and religion over nonreligion.” (3)

“As I see it, when a cross is displayed on public property, the government may be presumed to endorse its religious content. The venue is surely associated with the State; the symbol and its meaning are just as surely associated exclusively with Christianity.” (5)

“To non-Christians, nearly 30% of the population of the United States, . . . the State’s choice to display the cross on public buildings or spaces conveys a message of exclusion: It tells them they ‘are outsiders, not full members of the political community.’” (5)

“The principal symbol of Christianity around the world should not loom over public thoroughfares, suggesting official recognition of that religion’s paramountcy.” (8)

“At the dedication ceremony, the keynote speaker analogized the sacrifice of the honored soldiers to that of Jesus Christ, calling the Peace Cross “symbolic of Calvary,” where Jesus was crucified … The character of the monument has not changed with the passage of time.” (11)

“Holding the Commission’s display of the Peace Cross unconstitutional would not, as the Commission fears, “inevitably require the destruction of other cross-shaped memorials throughout the country.” When a religious symbol appears in a public cemetery—on a headstone, or as the headstone itself, or perhaps integrated into a larger memorial—the setting counters the inference that the government seeks “either to adopt the religious message or to urge its acceptance by others.” (16)

“If the aim of the Establishment Clause is genuinely to uncouple government from church,” the Clause does “not permit . . . a display of th[e] character” of Bladensburg’s Peace Cross.” (18)