There are many reasons Frances Ellen Watkins Harper might have gone from humble schoolteacher to renowned lecturer, but the one that tugs at me most has to do with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

The tipping point

The Fugitive Slave Act endangered not only runaway enslaved people seeking sanctuary in northern free states, but also free Black men and women who matched the descriptions of their enslaved counterparts. Maryland furthered this legislation by enacting a law that put any free Black person who entered the state in jeopardy of imprisonment or enslavement.1 A free man in Frances’s own city of Baltimore was kidnapped, sold into slavery, and eventually died before he could regain his freedom.2

One theory is that this is the knowledge that galvanized Frances and moved her private support of the Underground Railroad into the public spotlight.

Rather than recoil from the Fugitive Slave Act in fear, Frances spoke all over America—both in the North and the South—offering a rallying cry for change. She did not shrink or shirk but rose to the occasion with everything she could muster. In a letter to William Still, a fellow Black abolitionist, she wrote, “I have a right to do my share of the work. The humblest and feeblest of us can do something; and though I may be deficient in many of the conventionalisms of city life, and be considered as a person of good impulses, but unfinished, yet if there is common rough work to be done, call on me.”3

Frances’s tipping point might have looked a lot like one of mine.

My firstborn son was born the summer of 2016. My husband, Phillip, and I were in the middle of a cross-country move from Minnesota to Mississippi. The lease was up on our cute suburban duplex, and we were staying in a hotel until it was time to set off. Phillip had run out to grab us some food, and I was sitting in bed nursing Wynn and scrolling Facebook.

Philando Castile was killed that same day.

I scrolled in horror, processing the details of what had happened. He was shot by a police officer during a traffic stop in the very suburb Phillip and I had been living in for the past year. I immediately called Phillip to check on him, heart hammering in my ears, postpartum hormones rushing through my veins.

Philando Castile’s death was not the first such shooting of a Black man that I had ever heard of. It wasn’t the first one I had ever mourned. It wasn’t even the first one that had happened in a state where I resided.

But it was the first one that felt close. And I remember sitting on that bed, holding my brand-new baby boy, and thinking of how much everything had changed for me. I was now a mother of a little brown-skinned boy. My heart was not only out and about on the streets of Minneapolis in search of takeout, but in my arms.

I do not pretend to know the mind of Frances Harper (would that I did!), but I know what it feels like for something to hit closer to home than ever before. I know what it’s like for passion to spark and bleed out onto the page, and for the writing on the page to move one into the lectern. Bronze muse though I may never be, I have mused on so many of the words that Frances shared in myriad speeches, and I have felt the conviction of them deep in my own heart and life.

Frances did not work for fame and renown, but from a deep conviction that the work she was applying herself to was a worthwhile endeavor.

What Frances teaches us

Like more than one woman profiled in these pages, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was raised by a reverend and a teacher. She started working at fourteen and did not stop working until the day she died. She was married only four years before going back to supporting herself and her young daughter. And yet, if single motherhood was a challenge to the calling God placed on her life, Frances kept it to herself. She doggedly pursued her passions—lecturing, writing, and imagining.

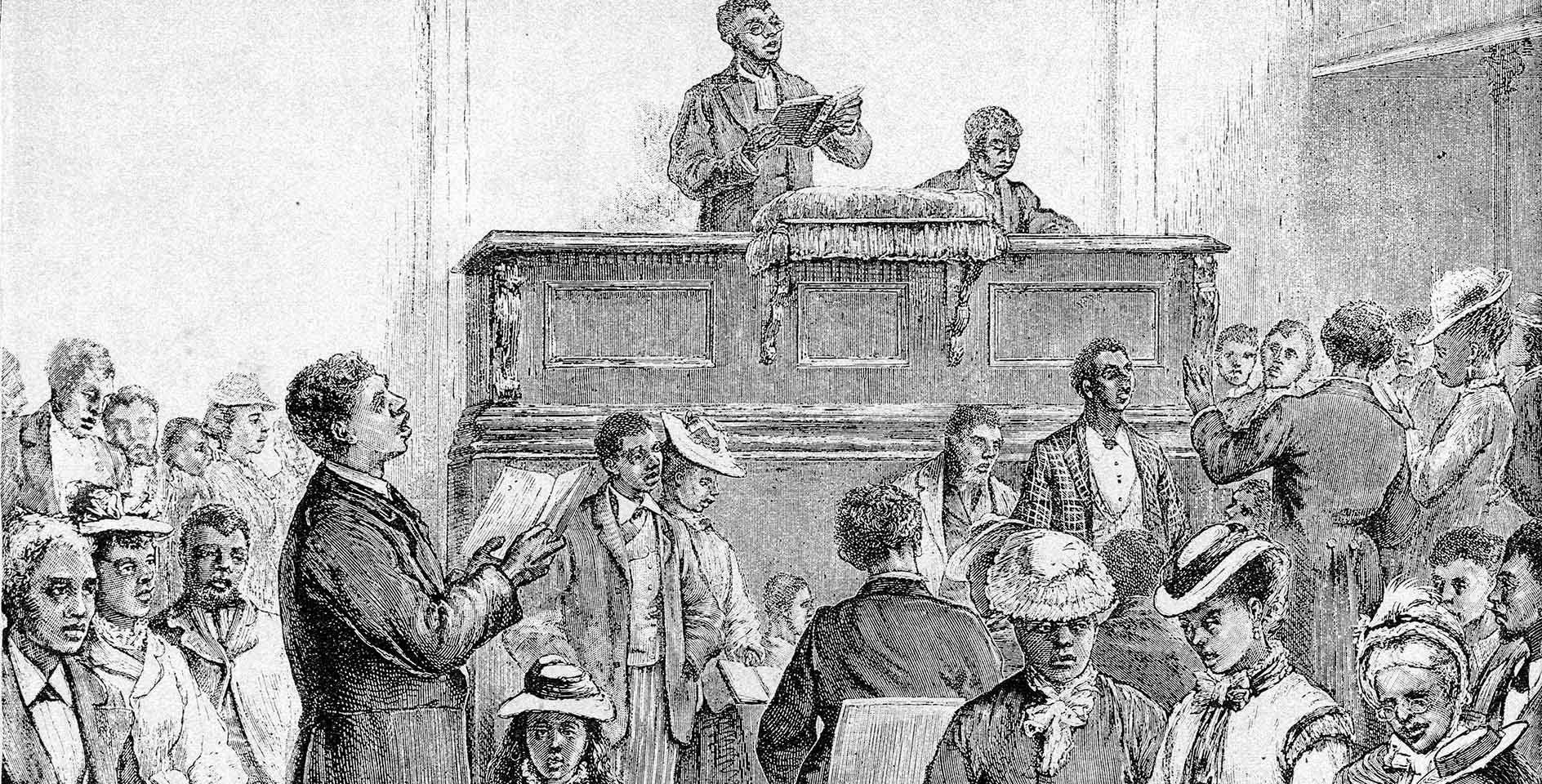

Her poise, rhetorical skill, and passion earned her the nickname The Bronze Muse, a title that pointed to the fact that Frances was a master of the English language in speech, poetry, and prose. She realized that she was an ambassador for her entire ethnicity every time she mounted the stage, and she did her people proud, her own ability for intelligent and articulate arguments proof of her claims of equality.

What I love about Frances is how thoroughly her poetic ability seeped into her rhetorical moments. She was every bit a poet in the lectern and every bit a principled orator in her poetry. Frances had a knack for uniting all parts of her skill in service for her cause.

I teach at a classical Christian school in Jackson, Mississippi. I’m excited to introduce Frances Ellen Watkins Harper to my students. We are very picky about the classical canon at my school, but we also realize that so many Black voices have been barred from that canon throughout history. Phillis Wheatley is the one Black poet the kids know—maybe Paul Laurence Dunbar, if they’re lucky, and later, Langston Hughes. But the canon should be full to bursting with a wide array of Black voices and a huge cross section of the Black experience.

Frances was not just a phenomenal speaker—she was a phenomenal writer. Her poetry and her storytelling abilities have stood the test of time, even when it seemed that time had forgotten them. In fact, just a few years ago, her first published book of poetry, Forest Leaves, was rediscovered. For one hundred and fifty years, we assumed that her words were lost forever. . . and yet they were found by a pesky PhD candidate who knew exactly where to look.

As much as I love playing hide-and-seek with the treasure trove of the influential Black women who have shaped us, it is my earnest hope that fifty years from now, a little Black girl who wants to grow up to be a writer doesn’t have to look far to find the work of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. Perhaps she will have had to memorize Bible Defense of Slavery or The Slave Mother. Maybe her teacher will have assigned The Two Offers in a short story unit. Perhaps in a class that focuses on nineteenth-century literature, Frances Harper’s Iola Leroy—the first novel published by a Black woman—will be found in its rightful chronology after Austen and the Brontës.

I do know that my own children and my own students will know her name. And perhaps, now that you’ve read her words, you can share her brilliance as well.

However, if I have learned anything from Frances, it is that no matter how quiet the record of her brilliance has been kept, it cannot remain silent forever. I did not know about her . . . until I did. And now that I do, I know to be incredibly grateful for her example and influence. And I know that there are myriad women like her, just waiting to be discovered. They are hidden gems and diamonds in the rough now, but they were outspoken dynamos while they lived. And their lives shine as examples to us all.

Footnotes

- Elizabeth Ammons and Frances Ellen Watkins [Harper], “Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825–1911)” Legacy 2, no. 2 (1985): 61-66. Accessed June 24, 2021, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25678939.

- Melba Joyce Boyd, Discarded Legacy: Politics and Poetics in the Life of Frances E.W. Harper, 1825–1911 (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1994), 40.

- Harper, A Brighter Coming Day, 47.

Excerpt from Carved in Ebony by Jasmine Holmes provided by Bethany House Publishers, a division of Baker Publishing Group. Copyright 2021. Used by permission.

“Chapter 4: Inspired by the Bronze Muse | Frances Ellen Watkins Harper,” from Carved in Ebony by Jasmine Holmes. pp. 70-71, 74-76, 79-80; 1,255 words (edited)