Two weeks ago, 30-year-old pastor and mental health advocate Jarrid Wilson took his own life, prompting many to consider why a vivacious young man with a thriving ministry and two small children would do think the world better without him.

He’s not alone. Last year, pastor Andrew Stoecklein of Inland Hills Church in California died by suicide. He was also a young father of three, who had preached a sermon on depression just 12 days prior to his death.

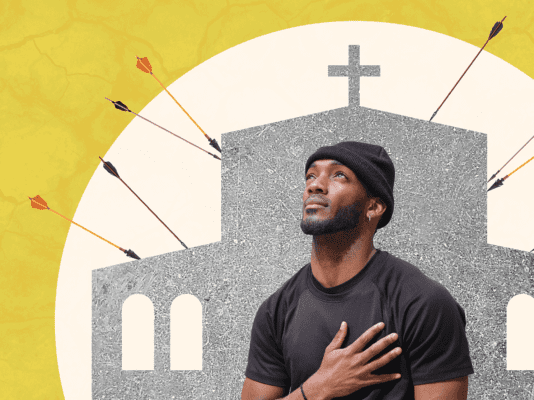

Faith has proved to be a solace to many church attenders, contributing to lower rates of suicide and higher rates of happiness, so it’s difficult to reconcile how a visible and engaged church leader isn’t among the saved. No easy answers exist, but there are a few telltale signs to examine in order to effectively grapple with how Wilson and other faith leaders came to such a point of desperation.

Hard aspects of the pastoral life

Mental illness, like depression that Wilson openly suffered from, is unquestionably the main component, but other aspects of the pastoral life contribute to why these leaders ultimately succumb to suicide.

Pastoring is one of the most high-pressure jobs in the nation. According to the Soul Shepherding Institute, an organization that exists to care for the mental well-being of pastoral leadership, 90% of pastors work 55-75 hours a week and 75% report feeling “highly stressed” on any given week. Most are managing family life with the demands of pastoral care, which usually comes with an unending stream of requests and responsibilities.

Most see a pastor at work on Sunday morning, but preaching is merely a fraction of their full scope of work. Pastors are also working with youth ministries, speaking at community events, meeting with individual congregants, leading a staff, crafting a church vision, officiating weddings, preaching at funerals, and helping specific ministries inside the church stay afloat. The time for personal devotion, reflection, or self-care is minimal, if even present.

The day of his death, Wilson preached at the funeral of a woman who had died by suicide. He was also at the helm of Anthem of Hope, an organization he founded to provide guidance and fight mental health stigma within the Christian community. He was 18 months into a new pastoral job at Harvest church, had written several books, and had a thriving online presence.

The pressure to succeed and appear like he was handling his mental illness was presumably higher than ever. Because people followed his honest tweets and encouraging online messages, it was easy to assume Wilson had the mental and spiritual support he needed. In reality, most pastors aren’t adequately cared for in this way.

“As a lead pastor, I can count on my hand how many times people have asked me [how I was doing with anxiety and depression],” said Shelter Cove Community Church Pastor Jeremy Oldenburger said in an online video posted days after he learned of Wilson’s death.

According to LifeWay Research, only 41% of pastors nationwide have received training to assist someone dealing with suicidal thoughts. I didn’t find any numbers on how many have been trained to deal with their own suicidal ideations—and that is extremely concerning. It might seem that one who spends his life helping others would know how to help himself, but a life in faith leadership demands a shiny external facade.

Rick and Kay Warren of Saddleback Church lost their son to suicide in 2013. Kay wrote this in the Washington Post after learning of a pastor’s suicide in 2017: “Who would pastor the pastor? The same spiritual leader who had been there for thousands of church members over the decades now wrestled in secret, feeling despondent, hopeless and utterly defeated.”

Pastors don’t get into their profession for the income. They often refer to their positions—not as jobs—but, supernatural “callings.” They are in the business of soul saving. Any perceived personal weakness could potentially damage that noble, ultimate goal. This is antithetical to the gospel message that we are all imperfect sinners in need of saving—and certainly not responsible for “saving” anyone. Pastors, however, are not immune to worldly ills, including an outsized desire to succeed or struggles with depression.

The Clergy Health Initiative at Duke Divinity School found that pastors experience depression at rates double that of the general population—and yet the resources available to them specifically are few.

“We are surrounded daily by people’s trials, pain and suffering—and if you aren’t taking care of yourself, over time—you can get numb, tired and weary, “ said one pastor I spoke with. “There’s this expectation that the pastor has it all together and it almost comes across as a weakness—and it’s difficult for [us] to find outlets to say, ‘I’m not doing well.’”

Additionally, admitting to struggles with mental health may cause fear of potential job loss or reputation downfall. That fear has valid roots. According to 2015 LifeWay Research, evangelicals are far more judgmental about suicide than the population at large with 44% saying they think suicide is selfish, as compared to 36% nationally.

Lastly, faith is by no means the only pathway to hope and healing for those who struggle. The Suicide Prevention Hotline may not pray with callers, but they are there for everyone who needs them. Sadly, pastors may feel uncomfortable attending non-faith-based support groups or seeking outside counsel because they fear being found out or manifest guilt that their faith isn’t enough. But, more awareness about the pressures of depression and anxiety among faith leaders, better resources aimed specifically toward them, and destigmatizing mental healthcare for this demographic will go a long way. Perhaps efforts of this kind would have been the safety net Jarrid Wilson needed to prevent his tragic end.

“People think that we, as pastors, are above the pain and struggles of everyday life. . . at the end of the day, we are just people like you,” said Harvest Church lead pastor Greg Laurie at a memorial service for Wilson last week.

Maybe that message is one to remember as congregants enter houses of worship this Sunday.