Conservative evangelicals stand in a particularly momentous position in the U.S. as various pressing domestic crises, conservative values, and sacred obligations converge over the issue of caring for our neighbors. This issue has taken on a greater significance as people have become more aware of wealth inequality and the lack of social mobility in our country. Our concern appears in the common refrain that the American Dream is no longer achievable for many Americans. One of the most popular “solutions” to this problem is universal preschool, which is designed to equip students to excel in school and then in the workforce.

Recently, New York Mayor de Blasio has announced plans to expand pre-kindergarten (beginning at age 4) in the city by selling bonds and taking money from charter schools. This isn’t a surprise, since universal pre-K has been one of de Blasio’s signature policies since before his election. He’s hardly the most notable politician advocating universal pre-K. Last year, President Obama announced an initiative to push for universal preschool, and when he did, conservatives roundly objected, pointing out the tremendous cost for an already over-budget federal government and the studies which have demonstrated the weaknesses in the Head Start Program.

There is a lot to criticize in Obama’s plan; it will increase our debt and will not likely improve the problem of social mobility, at least according to the research. But on the other hand, the status quo is unacceptable. As it stands, the “accident of birth is the greatest source of inequality,” according to Nobel prize-winning economist, James Heckman. And while we may object to efforts to create an “equality of outcomes,” such a dramatic disparity in opportunities for flourishing as we find between the poor and middle and upper class children is destructive.

While the rest of the country debates the effectiveness of Head Start and the tragedy of a calcified underclass, in Waco, Texas, a small Christian ministry has been sacrificially and willfully working to address generational poverty in their area by providing intensive, high quality, early childhood intervention (ECI) to the “least of these.” Their work is a model of how local churches can take up the needs of their specific communities in profoundly personal, humane, cost-effective, and gospel-driven ways which are fundamentally inaccessible for the State.

If the church in North America was to direct their benevolence resources into programs like Talitha Koum, they would effectively address (though not “solve”—nothing is that easy) nearly every major social ill which plagues our country while preventing the expansion of the federal budget. Of course, I understand the tremendous cost to the kind of project I’m describing, but when the crisis is properly understood, when we grasp what is at stake, the opportunity is astounding.

Researchers have identified a web of conditions which strongly predict whether or not a child born in poverty will succeed in moving out of poverty. Most of these conditions are related: family structure, racial and economic segregation, school quality, and social capital.

Rather than summarize the data which demonstrates how dramatically these conditions affect children, let’s consider a hypothetical scenario for a child born into a poor community.

You are born to a single mother who was herself born and raised by a single mother. Like most poor communities, there is high crime, low performing schools, and little engagement with private institutions (e.g., churches, nonprofits). Since your mother did not have a good parenting role model in her own mother, she lacks important parenting skills and knowledge. In part because of her own high levels of stress brought on by poverty, she struggles to provide you with the nurture and comfort a baby needs to bond and be sheltered from the negative influence of living in poverty. As a result, your home environment is unstructured, violent, loud, and uncertain.

From your earliest years, your brain is wired for a world of chaos. You are never taught self-control or delayed gratification, habits which your mother was never taught as a child either. She is less likely to read to you, and the number of words you hear will be drastically lower than your middle-class peers. If you are lucky, your mother has enough resources and skills to get you signed up for government assistance so that you have basic health care and food and perhaps you can begin attending a Head Start program when you are three. But by then you are already far behind your peers. You cannot self-regulate well enough in class to learn basic skills, which means when you enter kindergarten you are even further behind.

When you reach adulthood, you are less likely to have completed high school, more likely to be a single mother or have spent time in jail (for males), less likely to have a good job, and more likely to have health problems than your peers. Thankfully, at this point, a number of churches in your surrounding areas have good GED and job training programs which they devote considerable resources to, but since you are an adult, it takes a lot more effort for you to develop these skills. Odds are, your children’s childhoods will look a lot like your own.

Many pundits have correctly identified family structure as one of the main predictors of social mobility: If you are born to a set of parents who stay together, you are much more likely to be able to achieve your social goals. And so there has been a push by conservatives to stress the importance of marriage, and rightfully so. However, for people born into generational poverty, being told that marriage is important isn’t enough. They need deep, cultural, communal, and cognitive support that will equip them with the skills, habits and social capital necessary to get married for life and raise children in a healthy environment. And to be effective, these interventions need to begin at the earliest stages — 8 weeks old at the latest — when the brain begins to learn about the world, setting the neural pathways which will shape that child for life.

That is why President Obama and many others have been urging a dramatic expansion of preschool. Based on the research conducted by Dr. Heckman, advocates of universal preschool claim that for every one dollar spent on early childhood intervention, society saves eight dollars down the road in services like incarceration, increased healthcare costs, education, and entitlement spending. Even more appealing for conservatives, ECI was shown in Heckman’s work to be positively correlated with a variety of core social issues:

- Reduction in criminal participation later in life

- Increases in educational achievement in minorities and children in adverse home environments (poverty, single parents, etc.)

- Reduction in disparity between black-white incarceration rates by increasing the likelihood that black students complete more years of schooling (which lowers the probability of incarceration)

- Raises in future wages

- Increases in college attendance

- Increases in economic returns from their education

- Lowered rates of teenage pregnancy (since teen pregnancies among the poor account for a significant portion of abortions, this also should reduce abortion rates)

- Mothers who give more cognitive and emotional stimulation for their children—which prepares them to be successful

- Reductions in race and income gaps

But there are problems with this miracle solution proposed by Obama. As I mentioned in the beginning, Head Start programs have shown only very modest benefits, hardly the kind of dramatically life-altering benefits promised in Heckman’s research. Proponents of the programs respond that Head Start has had such modest results because it is underfunded; the programs Heckman studied were much higher quality and cost a lot more. Where Head Start will cost around $8,000 per year per student, the Perry study which produced Heckman’s much touted results cost closer to $20,000.

Ideally, voluntary, early childhood interventions would be run by local organizations, ones that can keep costs down, better meet the needs of particular communities, and build more meaningful relationships with disadvantaged youths and their families. This is the model of ECI at Talitha Koum.

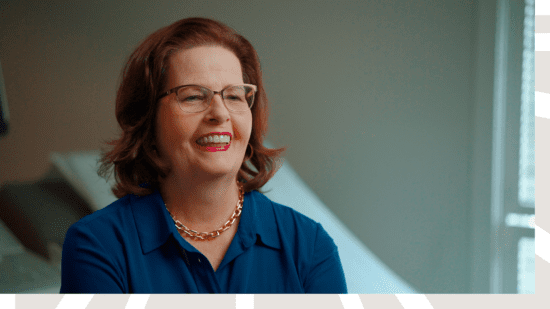

Begun by a very small church with several women dedicated to ministering to the poor in Waco, Talitha Koum is a “mental health therapeutic nursery.” They focus their efforts on the most needy families in the area—those who typically do not qualify for government assistance because they lack the resources or skills to apply. Beginning at eight weeks old, the children are cared for eight hours a day in small classrooms (six kids and two teachers per class) until they are ready for kindergarten. After they graduate from the program, they are paired with a local mentor who promises to help the child navigate life until they go to college or find good, full-time work. They would like to add a third leg to their work: in-home visits by licensed nurses, but it will require more funding. Currently, the foundation spends about $17,000 per child, per year—less than the Perry school but still a lot more than the proposed universal preschools.

When I visited with Susan Crowley and Donna Losak, two of the founders of Talitha Koum, I was struck by all the ways they were able to provide personal care for the children that would simply be foreign or impossible for most government programs. For example, when I asked about what qualifications teachers needed to work there, Crowley informed me that the most important characteristic they look for in teachers is a deep love for the children. They also require a bachelors degree of some kind and provide them with thorough training, but love is the necessary quality. As a private, local ministry, they also can adjust their practices based on the latest research. They can meet the spiritual needs of the kids because they are not a state agency. The children never have to lose care because their mother or father failed to fill out the appropriate paperwork or failed to look for work. At the same time, parents are encouraged to come to weekly parenting classes, where they are fed, and cared for, and encouraged. The result of this is that the workers at Talitha Koum have fostered deep, trusting relationships with these mothers, allowing them to minister to them and their children more personally and effectively.

One of Crowley’s mantras during my visit was that if the church would simply commit to caring for the needs of the most needy and vulnerable in our country for the first five years of their lives, we would have a profound impact on generational poverty. If local churches worked together to offer early childhood intervention programs, like what Talitha Koum has been doing in Waco, they would be more cost effective than the proposed state programs, but they also would be caring for the needy in more meaningful, intimate, spiritual and personal ways. And through this, they will be able to better proclaim the Gospel.

It seems inevitable that our country will try to combat generational poverty and all its great harms by investing heavily in early childhood intervention. We already see signs of the State moving towards such programs with President Obama’s 2013 State of the Union address and Mayor de Blasio’s expanded pre-K. Tragically and despite enormous costs, de Blasio’s pre-K initiative in New York will most likely have very modest results, particularly since it begins intervention at age four, so late in the child’s mental development. The question for the church is, will we allow the state to take the initiative, or will we take up this task and engender the kind of deep, redemptive healing that the state can only dream of?