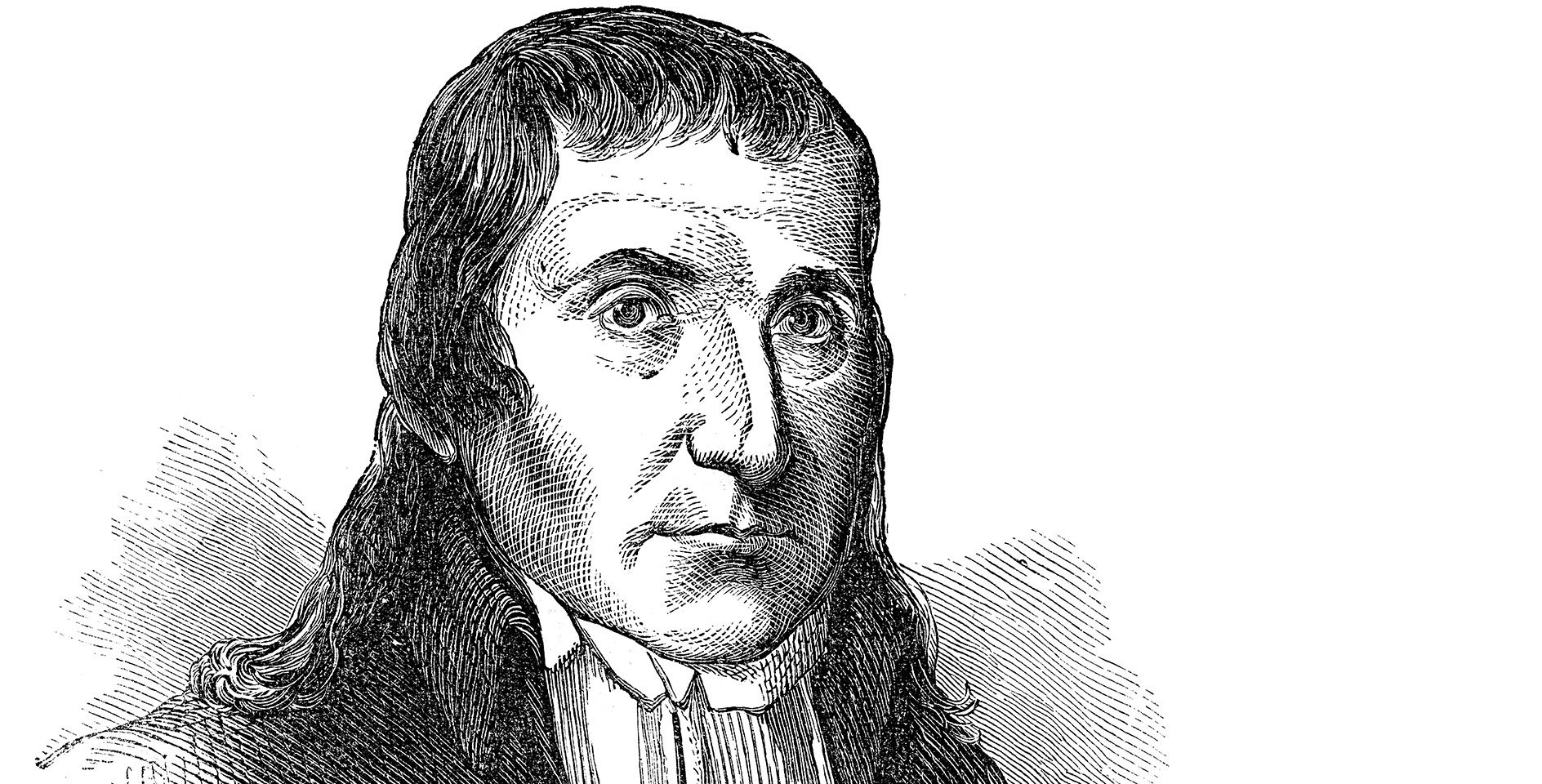

For those familiar with it today, the word “congregationalism” tends to evoke an American sense of personal liberty. Congregationalist churches, whether Baptist or otherwise, are typically understood to run on the wheels of democracy, investing ecclesial authority in the people rather than in the hands of the few. Thus, as the saying goes, congregationalism is as American as apple pie. However, while Jonathan Edwards was a Congregationalist pastor and has long been regarded as “America’s theologian,” this was by no means his brand of congregationalism.

Edwards’s doctrine of the church was conformed to the image of Puritanism more so than American politics. His vision of a biblical commonwealth, supported by his understanding of the local and national covenant, was grounded in a tacit church-state synthesis. In A History of the Work of Redemption, Edwards contended that the establishment of Christendom by Constantine was one of the four most significant events in church history. Therefore, his notion of religious liberty differed greatly from our modern Jeffersonian sensibilities. As Harry Stout explains, “In the Puritan state, religious freedom would be tolerated no further than the boundaries of ‘gospel order’ determined by the Congregational churches” (The New England Soul, 21).

Nevertheless, despite his belief in natural and social hierarchies, Jonathan Edwards was also a public defender of evangelical, revivalist Christianity. No 18th century figure, and perhaps no American ever, did more to vindicate lay religion as an authentic work of God than did Edwards. As a result, the man whom Isaac Backus affectionately referred to as “our Edwards” sowed many of the theological seeds which would inevitably grow into the religious liberty we enjoy and defend today.

In 1636, a century before the Great Awakening, the man who coined the term “congregationalism,” John Cotton, discussed the proper form of government in America. “Democracy,” he reasoned, “I do not convey that ever God did ordain as a fit government either for church or commonwealth. If the people be governors, who shall be governed?” This is the patriarchal, theocratic ideal Edwards inherited from his Puritan forebears.

A man between two worlds

Though American by birth, Edwards viewed himself as a subject of the British crown in a trans-Atlantic kingdom of top-down authority. Though a Congregationalist, Edwards also supported the Saybrook Platform, a Presbyterian-like measure which allowed ministers from the Northampton Association to regulate the admittance of pastoral candidates in churches, eviscerating local church autonomy. Politically speaking, Edwards was a social conservative for his era. “Tis no part of public prudence,” Edwards insisted, “to be often changing the persons in whose hands is the administration of government” (WJE 17:354-55). In Edwards’s mind, the strength of government was found in its stability, not necessarily in its protection of civil rights.

Still, George Marsden is undoubtedly correct that Jonathan Edwards was both a medieval and a modern. He was, to borrow Marsden’s words, a “conservative revolutionary” (Jonathan Edwards, 213, 253). Despite his penchant for order and his concerns over the excesses of revivalism, Edwards identified himself as a “zealous friend” of the Great Awakening, an itinerant and often outdoor movement that wrested power from the state-sponsored churches. In works like The Distinguishing Marks of the Work of the Spirit of God (1741) and Some Thoughts Concerning the Revival (1743), Edwards aligned himself with evangelical New Lights, even accusing those who would call into question the spiritual legitimacy of the revivals of “the unpardonable sin.” Decades before the political upheaval of the American Revolution that raised the “wall” between church and state, the social and ecclesial maelstrom of the Great Awakening began to tear at the fabric of the old-world establishment. And if George Whitefield was its public voice, Edwards was its apologist.

Rebirth of church-state relations

In a world of established religion, individual conversion was the single most socially leveling doctrine in the church, and from it Edwards developed a new ecclesiology that challenged centuries-old assumptions about church and state. Repudiating the policy of his predecessor and grandfather Solomon Stoddard, the “Pope” of the Connecticut River Valley, Edwards’s new requirement for admitting new members into the Northampton church included a credible profession of faith, the fruit of Edwards’s robust doctrine of rebirth. This Baptist-like idea of born-again believers being separate from the world was an indictment of the Halfway Covenant, a policy established in 1662 by Congregationalist churches wherein infant baptism was extended to the children of parents who were baptized but not professing.

In Edwards’s mind, the local covenant had slowly devolved into a kind of hereditary birthright. By insisting upon a credible profession of faith, and by challenging the traditionally rigid understanding of conversion morphology, Edwards was not only creating a space between church and state; he was identifying the Christian’s personal relationship with Christ—not their relationship to the local government—as the primary ground for church membership. This was nothing short of revolutionary in a society built upon the idea of interlocking church, local, and national covenants. So pivotal was this decision in the scope of American history that Edmund Morgan, in his biography of Baptist Roger Williams, looks forward to Edwards and states, “Like the followers of Jonathan Edwards a century and more later, Williams thought it compounded the wickedness of wicked men when they went through the motions of religion” (Roger Williams, 32). Armed with a theology of “religious affections,” Edwards sacrificed the presumptuous union of church and state (and ultimately his job) on the altar of born-again religion.

In Edwards’s view, a strict separation of civil and religious interests was injurious to the community because religion is necessary for a moral citizenry and a healthy society. Therefore, Edwards the Puritan would certainly have objected to John Leland the Jeffersonian when the latter boasted that “religion is a matter between God and individuals.” While Edwards affirmed the priority of individual faith and even defended “the freedom of the will”; his doctrine of the church was inescapably more corporate and even more civil than our 21st-century American minds would allow.

Still, in many ways, the life and ministry of Jonathan Edwards is the story of American evangelicalism in miniature. Renovating traditional Reformed doctrines with modern concepts, Edwards was both a child of Puritanism and a product of the Enlightenment. He was, as Perry Miller has insightfully observed, “not only a child of America, but, as such, is one of its supreme critics” (Jonathan Edwards, 179). Therefore, it should come as no surprise that Edwards’s notion of religious liberty was incredibly advanced for his time, yet still somewhat archaic for ours. Nevertheless, his insistence that our inner spiritual lives can be subjected to a public test, and that the church must remain distinct from the state in order to do so, has endured for centuries in America.