When Baptist U.S. Congressman Brooks Hays addressed the Baptist World Alliance in Copenhagen in 1947, he insisted that Baptists could not compromise on religious liberty. However, he intriguingly argued, “[Baptists] do not identify our faith with governmental or economic patterns.” Hays went on to outline a deferential sort of positioning toward the state which would involve a posture of trust regarding matters such as taxation. From his perspective, it had been the better part of the contemporary Baptist attitude to trust popular governments. As long as the state gave due respect to individual conscience, then prudence would be the best guide (as opposed to something more like a Baptist ideology).

Hays’ view fit well with traditional Baptist priorities, which have been most focused on evangelism, missions, and religious liberty. Religious liberty has been important both because of the emphasis Baptists place on the regenerate church and their desire to maintain a clear field for evangelism and missions. Unlike the Catholic church, Baptists do not have a long history of lining out detailed strictures of social thought. The reason for that lack of focus was not negligence, but probably something more like a prudent calculation: not including a comprehensive political program as part of the faith would pave the way for acceptance of missionaries by foreign governments and their people. Less attention to politics helps reduce suspicions that the gospel is simply a cover for smuggling in ideological control of some kind. The experience of Catholic missionaries in Japan centuries ago is instructive in that regard.

Of course, 1947 is a different place in time than 2024. Baptists were happy advocates of a growing appreciation for religious liberty in a nation building out constitutional protections, with the First Amendment receiving the most attention. The Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade had not yet happened. Neither had the sexual revolution or the broader tornado that hit traditional conceptions of human sexuality. Ecology had not yet become a major concern. The biggest moral crisis in the late 1940s was probably civil rights, as Jim Crow laws and segregation still persisted in the American South. If we wanted to take the cynical view, we might argue that staying out of politics was a way for a church largely located in the Southern United States to avoid unwelcome controversies. Jerry Falwell, in the years before his political awakening, insisted that he would not use his pulpit to address either race or nuclear war, as politics should not enter into preaching. He obviously came to feel differently in the 1980s with the founding of the Moral Majority.

We should prioritize life and religious liberty

Today, the situation is different in many ways. The issues of the most immediate interest to Baptists today are abortion and religious liberty. The rationale for focusing on abortion is obvious, although it took Baptists a while to catch up with Catholics on the issue in the immediate aftermath of Roe. The film, Whatever Happened to the Human Race?, produced by Francis Schaeffer and future Surgeon General C. Everett Koop helped spur Baptists to join the pro-life coalition. They came to see the preborn child as an innocent party who is also a bearer of God’s image. Since the battle for control of the Southern Baptist Convention that raged mostly in the 1980s, the SBC has been stalwart in its defense of preborn life. Indeed, since the founding of The Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, pro-life advocacy has been a top priority for Southern Baptists. Now that the Supreme Court has overruled Roe, the issue has reentered the realm of democracy in a much more immediate way. Supreme Court nominations served as a kind of distant referendum on the issue, but now the voters of the different states are taking the issue on directly. More recent contests have not gone well for the pro-life movement. There are obvious indications that the Republican party is wavering on the matter, as it appears pro-life advocacy may not make for good retail politics. Meanwhile, the Democratic party has doubled down on its support for abortion rights.

What should Baptists and other Christians do to protect preborn children?

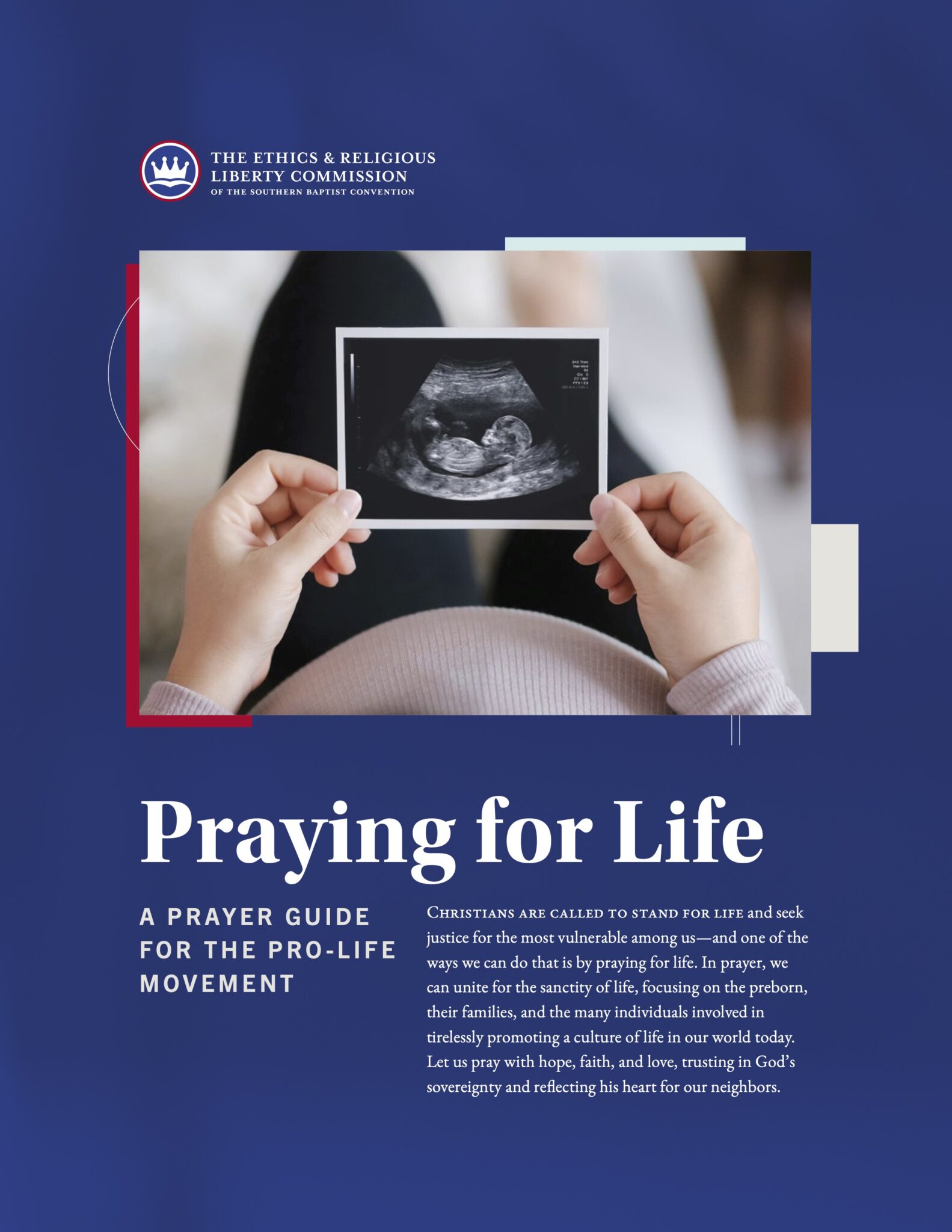

The answer is that we are at the beginning of the battle to protect preborn children. Everything that has happened up until now was merely a prelude. Anyone who thought reversing Roe would put the issue to rest was misguided. What has happened is that the life issue is now open to democratic consideration. We have only begun to advocate on behalf of the preborn. The reaction of the parties has been terribly discouraging, despite the continuing development of our knowledge of fetal development. Somehow we live in a world where an preborn child is only considered human and morally significant if that child is wanted by his or her mother. Such children may be celebrated in ultrasound images posted on social media or disposed of in medical waste dumpsters. Churches must enter into this issue through works of mercy, education, and political advocacy. Most importantly, we must not waver out of a desire to win elections in the short term or to court cultural favor. Seeking to protect innocent, preborn life is a very high priority for the Church and has been since the early days of its existence in the classical world. Rather than being disillusioned by the reaction to Roe’s reversal and the valorization of abortion currently in vogue, we must renew our commitment. There is no post-Roe rest.

What has happened is that the life issue is now open to democratic consideration. We have only begun to advocate on behalf of the preborn.

Hunter Baker

What should Baptists and other Christians do to protect religious liberty?

Religious liberty also continues to be a major concern for Baptists, as it has always been. Baptists have sought to protect individuals from church establishments that can coerce religious belief and participation. However, the nature of the religious liberty challenge has changed. Established churches present little threat in a secularized culture that emphasizes personal autonomy. Instead, the battle for religious liberty today focuses on the right to conduct life activities with a sensibility that may clash with that of the dominant culture or politics. As a consequence, religious liberty efforts are primarily focused on protecting Christians trying to live an integrated life, where their faith shapes and dictates their participation in public life.

Religious liberty efforts are primarily focused on protecting Christians trying to live an integrated life, where their faith shapes and dictates their participation in public life.

Hunter Baker

What form does that take? Through much of the 20th century, Baptists promoted an understanding of the First Amendment’s religion clauses that put a burden of proof on the state to justify its impositions on the consciences and beliefs of people. Thus, we saw the Supreme Court deliver a series of decisions reinforcing that understanding. The state, then, would be required to show it had a compelling interest and had achieved that interest in the least restrictive way, with accommodations made wherever possible. There is little question that this late 20th century state of religious liberty jurisprudence represented the apex of constitutional protection. That understanding came under fire when a drug case involving ceremonial use of peyote seemed to roll free exercise protections back to a minimal status. In the last act of truly bipartisan regard for religious liberty as it had come to be understood toward the end of the millennium, Congress nearly unanimously passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) with the signature of President Bill Clinton. Had that law not been passed, Hobby Lobby would have later been hounded out of business by the federal government with its HHS mandate, which attempted to force the company to purchase abortifacients against the owners’ faith and conscience.

When the Supreme Court struck down the application of RFRA with regard to the states, religious liberty advocates tried just a few short years later to pass another law to fully rebuild protections so that both states and the federal government would be restricted in imposing upon free exercise rights. It was no longer possible to gather the same coalition. The reason was simple. By the year 1999, gay rights groups opposed such legislation because they deemed religious liberty to be a license to discriminate. This second effort could yield only a much more limited law that protected churches from zealous zoning commissions and reinforced free exercise rights of prisoners.

Today, the religious liberty issue revolves around the status of Christian and other religious institutions, most notably in the area of education. Christian schools and colleges, for example, are determined to preserve the classical and orthodox understanding of human sexuality set forth in the Bible. They are resolved to teach that understanding and to hire faculty and other employees who agree with it. As a result, they stand as a major obstacle to proponents of the revolution of human sexuality, whose agenda has extended well beyond same-sex marriage to touch upon matters that include athletics, locker rooms, and bathrooms.

It is important that Baptists continue in their historic commitment to religious liberty now, not to prevent a state church from enervating true belief and blocking organic ministry, but instead to prevent a new secular, materialist orthodoxy from imposing itself upon all manner of endeavors.

Hunter Baker

It is important that Baptists continue in their historic commitment to religious liberty now, not to prevent a state church from enervating true belief and blocking organic ministry, but instead to prevent a new secular, materialist orthodoxy from imposing itself upon all manner of endeavors. This new kind of establishment would seek to replace the free exercise of religion with something much more limited in scope such as “freedom of worship.” Instead of protecting faith in the great vista of human activity, freedom of worship would focus much more narrowly upon the formal things that happen in the sanctuary and on church grounds on Sundays or Wednesdays. Christians should strongly resist this kind of interpretation.

How should we be thinking about voting, life, and religious liberty?

We should have a cathedral-building mindset

Given the urgency of these two issues, life and religious liberty, what should Christians be doing? How should we be thinking about voting and the issues?

I would argue that we should not focus as much as we might tend to on simple retail politics. Many of us have been shocked to see how quickly we can be abandoned on a fundamental human rights issue such as the sanctity of life when the issue is perceived by the political class as a loser. Religious liberty is the same. It is not the business of the Church to focus narrowly on winning elections that arrive every two years, just to watch fragile victories fade away.

Instead, we might think in terms of the people who spent their lives building cathedrals, which they would never actually see completed because the project took centuries.

- We should be laboring to change the thinking of our culture in fundamental ways. That means we have to help our fellow human beings understand the deep injustice of treating an preborn child like a parasite or an intruder into the womb of his or her mother.

- We also need to recommit ourselves to building out a broad and deep appreciation for religious liberty. We should recover the great John Courtney Murray’s argument for the religion clauses of the First Amendment as “articles of peace” that help us to live together.

- It is also important not to give in to the frustration some of our friends to the right may have, which leads them to look back to a state church as an answer to a series of cultural and political losses. Instead, we need to continue advocating for the free church inhabited by free individuals who live out their lives without having their faith and convictions burdened by an overzealous government which seems to want to regulate ever more of life.

We need to continue advocating for the free church inhabited by free individuals who live out their lives without having their faith and convictions burdened by an overzealous government which seems to want to regulate ever more of life.

Hunter Baker

Let me return to Brooks Hays and his good advice about Baptists embracing minimal politics in service of keeping doors for the promulgation of the gospel as wide open as we can. There is a lot of wisdom there. And it is true that much of politics is really a matter of prudence where we should all have a lot of latitude to think about, discuss, and perhaps even come to different conclusions.

But Hays said Baptists must insist on religious liberty. We should take that view as well. It is a key Baptist distinctive, deserving our continued advocacy and attention. But it is not the only issue deserving our attention, then or now.

There was another issue of fundamental justice in Hays’ time: segregation. We know that the Baptist church had a mixed record at best on that point. It is not hard to understand that such failures come from a tendency of human beings to confuse the values of the prevailing culture with the demands of the gospel and a right understanding of how image-bearers should be treated. With regard to the sanctity of life, our church got off to a rocky start in the immediate post-Roe period but quickly came to understand the implications of creating a market for the termination of pregnancies. If we now feel we were slow, far too moderate, or even obstinate with regard to critical matters of race, we can demonstrate much greater commitment when it comes to the preservation of the most disenfranchised, vulnerable group of humans in our society.

We need to participate in our nation’s civic process. We should vote, organize, speak, write, and all the rest. But the greater need is for us to be faithful over the long term and to bring as many people along with us in the process. We will not create a political coalition in order to win a contest, but rather to vindicate our greater moral and spiritual responsibilities. Christ is King. We should live our entire lives, including our political lives, as though we know it.