Editor’s note: This is the first article in a series on what Christians should know about ethical theories. This and future articles can be found here.

“We have two kinds of morality side by side,” said the philosopher Bertrand Russell, “one which we preach but do not practice, and the other which we practice but seldom preach.” Russell was an atheist, but his aphorism is all too applicable to many Christians. Too often we preach a type of moral theory that not only differs radically from that which we practice, but with which we would not want to be associated. For example, we would rightfully reject—at least in what we “preach”—that “the end justifies the means.” But in practice we do tend to justify the unjustifiable if it leads to an outcome that we desired. To bring our preaching more in line with our practice, we need to develop a clearer idea of ethical systems and how they are connected to the Christian faith.

Ethics is the study and application of moral principles that govern a person’s behavior or conduct. The sub-branch that focuses on what action a person should take is normative ethics. In this series, we’ll look at several of the most common ethical systems within normative ethics (such as deontology, consequentialism, and virtue ethics), consider their strengths and weaknesses, and compare them to a baseline standard, which we’ll call “biblical ethics.” By developing a clearer understanding of ethical systems, we can better understand how to apply them in our own lives—or whether they should be rejected entirely.

What is Christian ethics?

This application of ethics in our everyday lives primarily involves the process of moral decision-making, a process which requires us to primarily answer two questions: “What should we do?” and “What should we be?” For a Christian, the answer to those questions should ultimately be: “What God has commanded me to do—to obey him” and “What Jesus wants me to be—to be more like him.”

In John 14:15, Jesus said, “If you love me, you will keep my commands.” That’s not a suggestion—Jesus framed it as an imperative. Those who love Jesus will keep his commandments. The corollary is that those who do not keep his commandments do not truly love Jesus. Loving Jesus is the minimal standard for identifying as a Christian. If you do not truly love Jesus—if you do not even attempt to keep his commandments—you should not call yourself a Christian.

The central paradigm for Christian ethics is thus union with and conformity to Jesus, primarily through the Spirit-driven process of obeying all that Jesus has commanded of us. As the Christian ethicist John Murray said, “If ethics is concerned with manner of life and behavior, biblical ethics is concerned with the manner of life and behavior which the Bible requires and which the faith of the Bible produces.”

Because Christian ethics should be rooted in Scripture, all Christian ethics should be biblical ethics. But because that is not always the case, we’ll use the term biblical ethics to refer to a specific form of biblically based Christians ethics.

What exactly is biblical ethics?

Biblical ethics, as defined by Murray, is the study and application of the morals prescribed in God’s Word that pertain to the kind of conduct, character, and goals required of one who professes to be in a redemptive relationship with the Lord Jesus Christ.

Biblical ethics is bibliocentric (Scripture-centered), theocentric (God-centered), and Christocentric (Jesus-centered). As David W. Jones explains in An Introduction to Biblical Ethics, this means our approach to biblical ethics should:

- Not only describe what the Bible says but treat what it says as authoritative, inerrant, relevant, and necessary;

- Not only accept biblical teaching as a good way of doing things but as applying eternal, divine, moral laws to everyday life; and

- Not only embrace a theistic worldview but affirms the uniqueness of Christ as the way, the truth, and the life—not only for Christians but for everyone everywhere.

There are at least five distinctives of biblical ethics, says Jones, that make it different than other ethical systems:

- Biblical ethics is built on an objective, theistic worldview. In other words, biblical ethics assumes the presence of a fixed moral order in the world that proceeds from God. Therefore, advocates of biblical ethics affirm the existence of universal, moral absolutes.

- Biblical ethics is not a means of earning favor with God but rather is the natural result of righteousness already imputed by God.

- Biblical ethics seeks to recognize and to participate in God’s moral order already present within the created order and in special revelation.

Biblical ethics affirms that immorality stems from human depravity, and not primarily from man’s ignorance of ethics or from socioeconomic conditions. - Biblical ethics is the process of assigning moral praise or blame, and incorporates conduct (that is, the what), character (the who), and goals (the why) of individuals involved in moral events.

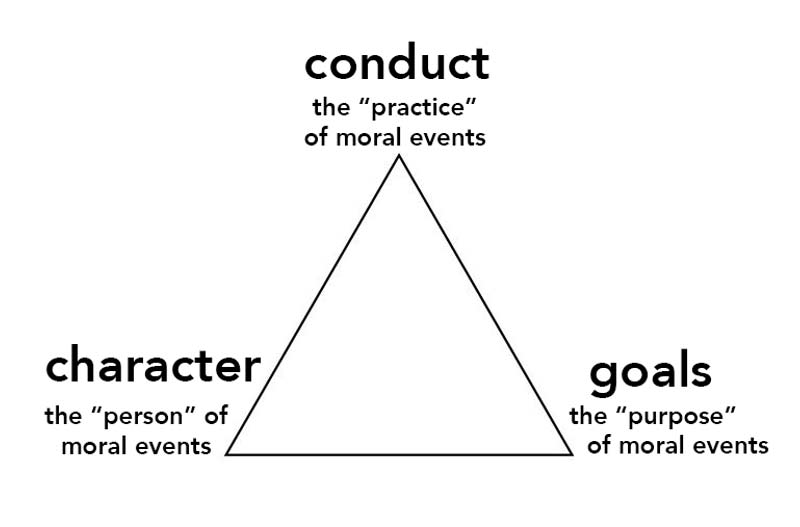

All three of these last three elements—conduct, character, and goals—are interrelated and can be visualized in this moral events triangle, says Jones.

The first corner of the moral events triangle corresponds to conduct, that is, the “practice” of moral events. Moral conduct is based on an ethical rule or principle and focuses on external acts and behavior. Conduct is typically an orientation of person-to-person.

The second corner of the triangle stands for character, that is, the “person” of moral events, and focuses on motives and internal disposition. Character deals with the things inside each person—that is, a person’s self-relations. Character is an orientation of person-to-self.

The third corner of the triangle represents goals or the “purpose” of moral events, which is oriented toward a purpose and focuses on design or intended end. In biblical ethics goals deal with relations between man and God. Goals are an orientation of person-to-God.

Our character and our conduct are ultimately oriented toward the end goal of biblical ethics—the glorification of God. In John 14:21 Jesus taught his disciples, “The one who has my commands and keeps them is the one who loves me.” And in Matthew 5:16, in his Sermon on the Mount, Jesus instructed his listeners, “In the same way, let your light shine before men, so that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father in heaven.”

Therefore, a primary way Christians love and glorify God is to keep his commands and perform the good works that flow from godly character and actions.

How do we know when an action is moral?

In determining whether an action is moral, we first start at the top of the moral events triangle with conduct, the “practice” of moral events. When faced with a moral scenario, the first question that should be asked is, “What ethical rules or principles apply in this particular situation?” We must know and understand the rules/principles as well as the relevant facts and context about the situation, what we’ll call the “fact pattern.”

Once the applicable moral norms are identified we then move to the next point on the triangle, which concerns character—the “person” of moral events. In the process of making a moral decision, believers ought to consider their motives and ask the question, “Am I acting out of love for God and love for neighbor?”

Finally, we get to the last step in the process of moral decision making. As we noted earlier, the end goal of biblical ethics is the glorification of God, so we need to answer the question, “What path, choice, or answer would bring the most glory to God?”

A primary way Christians love and glorify God is to keep his commands and perform the good works that flow from godly character and actions.

The right path is to keep the moral law out of a love for God and neighbor with the intent of bringing glory to God. We also need to make sure we have the proper order and connection between love of God and love of neighbor: Love of God comes first, and love of God leads to love of neighbor.

In the next article in this series, we’ll look at moral decision-making, including how we know which rules or principles apply to a given situation, what we do when moral acts conflict, and the role of conscience.

For further reading

- John Murray, Principles of Conduct: Aspects of Biblical Ethics

- David W. Jones, An Introduction to Biblical Ethics