William F. Buckley famously said of the mission of National Review, “It stands athwart history, yelling Stop.” Ben Sasse’s new book, Them: Why We Hate Each Other–and How to Heal might similarly be summarized as one that stands athwart society, pleading, “Don’t you see what’s happening?”

Them “is not about politics,” Sasse, a United States Senator, tells readers (3). And by that he means the book isn’t designed to persuade readers of particular policy prescriptions. This is not to say politics has nothing to do with the book. It does, very much so, but politics is in view as a symptom rather than as the disease itself.

What is the primary problem?

Loneliness.

The problems

Sasse devotes the first four chapters of Them to explore the problem of loneliness and its wide-ranging societal effects. “Our world is nudging us toward rootlessness, when only a recovery of rootedness can help us,” Sasse writes (15). This rootlessness leads to loneliness. Lonely people seek out identity and community somewhere, even if it means (which it has) finding “home” in a terrible place—like politics. In turn, when politics becomes ultimate then Americans become fanatical, lots of ugly things start to happen, and our republic atrophies.

This loneliness is seen both at home and at work. “We’re hyperconnected, and we’re disconnected,” Sasse notes (28), and the increasingly mobile economy, in which men and women move from job to job and place to place tends to contribute to our rootlessness. “We need to be needed,” Sasse argues regarding the importance of jobs (62), but when identity-shaping vocations are stripped away, depositing rootless people into nonfunctioning communitiunities, the net effect is not a happy one.

Further, Sasse considers what he calls anti-tribes: “We’re meant to be for things and people, but absent that, most of us will choose to be against things and people, together, rather than to be alone” (72). Nowhere is this seen more clearly than in our politics and media. News outlets (on both the left and right) capitalize on this and have built an entire business model around it: “Hosts, producers, and executives know that Americans are primed to despise each other—they just need a target. And anger is intoxicating” (108).

In a memorable and newsmaking section, Sasse chides Fox News host Sean Hannity as an example of fostering anti-tribes on his shows: “The storyline is simple: Liberals are evil, you’re a victim, and you should be furious. Hannity tells a lot of angry, isolated people what they want to hear” (106, cf. 121). To be sure, Sasse assigns blame to left and right, while also assuring that there are many journalists who work hard trying to do their jobs well. Regarding President Trump, Sasse sharply criticizes “the president’s lack of interest in facts,” (126) but at the same time he argues that the problem isn’t isolated to the current Commander in Chief: “Donald Trump created none of this—he simply plays the fiddle ‘better’ than anyone has ever managed before” (125).

The solutions

In the final four chapters of the book, Sasse provides solutions to these wide-ranging problems. These prescriptions are extensions of one overarching argument: we need to remember what it means to be American, namely, that America is first and foremost an idea, “a commitment to the universal dignity of persons everywhere,” (134) and this idea must be shared and sustained for our republic to survive.

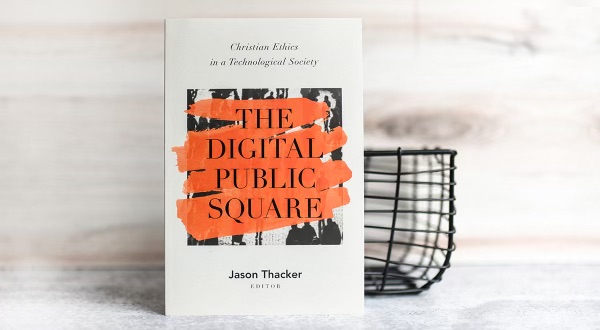

In these prescriptive chapters, Sasse takes on technology. He’s “Christmas-morning giddy” about many of these new technologies, but fears that we haven’t “reflected adequately on the downsides” they bring (177). In one of the most useful portions of the book, Sasse offers sixteen rules his family observes to make sure technology is a servant but not a master (199). Sasse counsels readers in the title of one chapter to “Buy a Cemetery Plot,” not so much because he’s concerned about the funeral industry but because too often Americans “look for reasons to avoid investing our time or energy or resources in a particular place or at a particular moment” (212). If we invest ourselves wherever we are, though, we become more rooted to place and more committed to our neighbors. Regardless of where we are, “we need to figure out a way to realize a sense of home” (236).

In all—as Sasse sketches in a substantive concluding chapter—healing entails at least three basic things: (10 rejecting anti-tribes; (2) putting politics in its proper (subordinate) place; and (3) finding our identity more in people and place than in politics.

Them is the right book for the country

Them feels like the sort of book that was somehow co-authored through the ages by Augustine, James Madison, Neil Postman, and Wendell Berry. Prophetic without being preachy, the diagnosis Sasse provides is at the same time both self-evident and yet desperately needed.

Though there has been no shortage of voices questioning the hold that screens and social media have on our lives, Sasse covers this terrain efficiently and deeply in a way few others have. Additionally, the list of sixteen truths that govern the Sasse family’s approach toward technology, family, and friends (199) is worth the price of the book in and of itself—even if just as a conversation starter. Beyond the book’s primary argument about loneliness and localism, some of the most thought-provoking aspects of the book surround the coming disruption the digital economy will bring to the American workforce. Clear-eyed and thoughtful, Sasse canvasses artificial intelligence, automation, and the digital economy in a way that many readers will likely have never considered.

Perhaps the most significant element of the book, though, is the second section, unveiling the business model of so much of our mass media. As one who works in the public space and runs a media relations department, I’ve experienced this on both the left and the right. “Are you willing to say,” I’ve been asked by a show producer, “that this elected official is evil and hates Christians?” “Of course not,” I’ve answered, “but I’m happy to say where we disagree strongly with his political convictions.” “Thanks,” the producer tells me. The call ends, and the show moves on until they find a Christian personality who’s willing to stick more closely to their script. Sasse, however, peels off the veneer in a way that shows readers the “game” that’s being played (122), or perhaps even more so, the way Americans themselves are being played. Interestingly enough, some in the media world have lashed out at Sasse in the wake of this book’s release—offended, outraged, and telling their listeners all about it. Of course, by doing this, they prove Sasse’s point. Sasse’s critique, however, is not just of this business model, but also of its consumers—because the plan doesn’t work unless the demand for titallation exceeds the demand for truth. A far cry from cynicism or defeatism, though, Sasse is right to note that there is still a way out of the mess—one that starts with reforming our habits and affections.

Them is the right book for the church

To be clear, while Sasse is an evangelical Christian, Them is not a Christian book, nor is it overtly theological. That said, it is deeply resonant with a Christian worldview, and throughout it raises a number of questions that might be uniquely helpful for Christians and churches.

For starters, Christians ought very much to consider who “we” are. That is to say, if part of the problem in our society is the demonization of “them,” then one of the questions we need to answer is, “Who are we?” Too often, American evangelicals are tempted to identify more closely with our political tribes than with the people from the tribes, tongues, and nations with whom we will spend eternity. Politics just feels more real. And that’s a problem. In churches where it’s more likely that a break from political orthodoxy will cause greater alarm and fiercer division than will a break from, well, actual orthodoxy, we have a real problem. In Them, Sasse points to Alexis de Tocqueville’s crediting the United States success to their “voluntary associations,” what Edmund Burke called the “little platoons” of society (235). Sasse rightly stresses their importance for our republic, but for those of us in Christ, the primary “little platoon” in which we find ourselves is the local church—existing as it does as the colony of a coming (and advancing) kingdom. Them ought to serve to remind us of where our primary allegiance resides.

Not only that, but Christians ought to consider how, and by what, they are being shaped. If nothing else, Sasse’s book shows that great wisdom and discernment is needed when it comes to media consumption. The lesson from Them is not, “Don’t trust the media.” Instead, the lesson is, “Don’t you see what’s going on here?” What’s going on here, is, too often, a competition for clicks and an invitation to outrage. If we know that, we’ll be slow to baptize outlets or elected officials or media personalities and be quick to understand our neighbors who may differ from us—seeing them not as “them” (as enemies to be vanquished) but first and foremost as either present or potential brothers and sisters in Christ toward whom we should have compassion. More still, wisdom applied to what we consume will help ensure that our political convictions are formed first and foremost by Scripture rather than drive-time personalities.

All told, Them is thoughtful, provocative, and sorely-needed in our outrage-drunk moment. It’s sure to make some uncomfortable, but a prophetic word always does. It may not be the book that Washington wants. But it’s the book that America needs.